Night-shift work and Light-at-Night

At a Glance

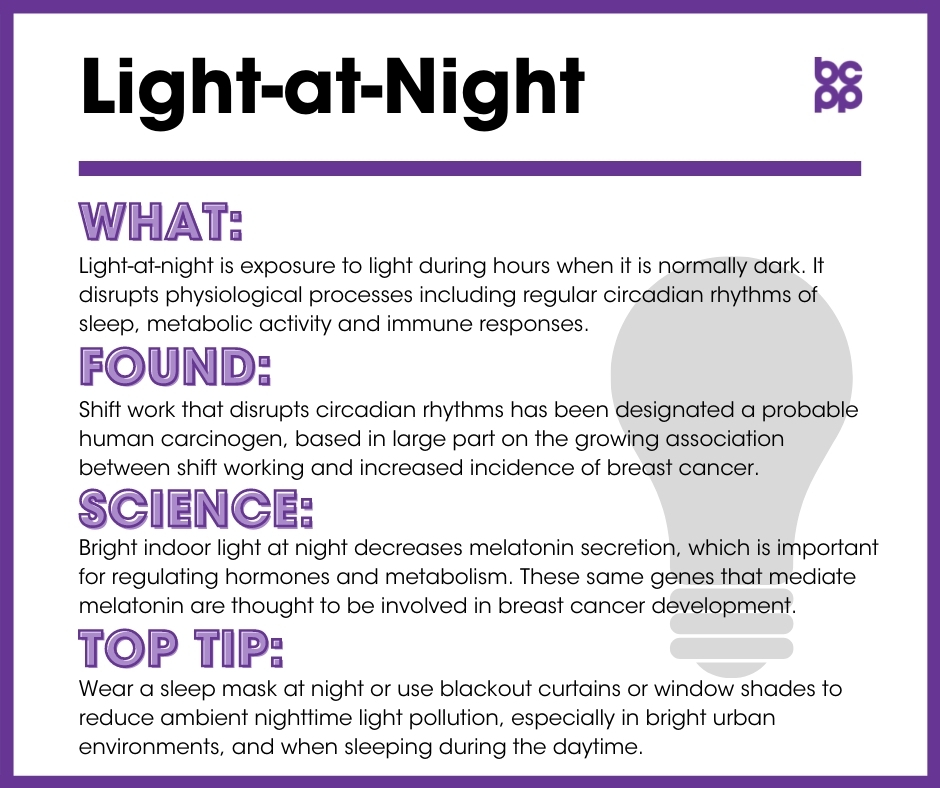

Light-at-night (LAN) is exposure to light during hours when it is normally dark. This exposure is common for evening and night shift workers, as well as for people living in urban areas where there is significant light pollution.

Exposure to light-at-night has been linked to an increased risk of developing breast cancer.[1],[2]Recent data suggest that exposure to smartphone and computer screens into the evening, before heading to sleep, may also be an important source of LAN.

What is light-at-night?

Exposures to light, at times of day when historically people have been mainly exposed to dark, is often referred to as light-at-night (LAN). LAN leads to disruption of physiological processes including regular circadian rhythms of sleep, metabolic activity and immune responses. One of the most studied sources of LAN is engagement in night shift work (NSW), both constant and rotating. Shift work that disrupts circadian rhythms has been designated a probable human carcinogen, based in large part on the growing association between shift working and increased incidence of breast cancer. Another area that is receiving recent attention is the effects of increased exposure to ambient light at night, mainly from urban and street light sources, on breast cancer risk. A major explanation for these relationships is that exposure to light-at-night, common for night shift workers, can lead to a decrease in the secretion of melatonin, a hormone that usually helps suppress the development of cancer. Other interacting factors may include disruption of sleep patterns and immune system responses, and increases in physiological and psychological stress.

What evidence links light-at-night to breast cancer?

- In 2007, the International Agency for Research on Cancer concluded that shift work that disrupts circadian rhythms is probably carcinogenic to humans, based in large part on the growing association between shift working and increased incidence of breast cancer.[3]

- In 2021, the U.S. National Toxicology Program (NTP) released its systematic review and evaluation of the hazard potential of exposure to light-at-night. It concluded, with ‘high confidence’, that persistent night shift work which results in the disruption of circadian rhythms, can cause breast cancer.[37]

- One study of occupation and cancer in Britain calculated that for 2012, night shift work was linked with 4.5 percent of breast cancer diagnoses and deaths.[4]

- Despite this strong determination of probable carcinogenicity of shift work, controversies remain in the literature in part because studies define shift work in vastly different ways. Some gather detailed information on the type of schedule and duration of shift work while others simply ask if one ever worked nights.[5]

- In a study of Danish nurses, effects of night shift work on breast cancer risk were greatest for women who worked rotating hours that included the overnight (as opposed to the evening) shift, and for those who worked 12-hour shifts that alternated day and night work, as compared to shorter work periods.[6]

- Flight attendants are another occupational group who frequently engage in night shift work. Compared to a national sample of women who were not flight attendants, those whose worked in this occupation had a 50% increase in risk of developing breast cancer (in addition to melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancers). In addition to increased night shift work, flight attendants are also often exposed to a variety of environmental toxicants, including cosmic ionizing radiation suggesting possible interactions between a variety of factors, including shift work, in affecting breast cancer risk.[7]

- Risk of developing breast cancer increased for women who worked night shifts for more than 4.5 to 5 years, and for those who regularly engaged in night work for at least four years prior to their first pregnancy, thus before the time when their mammary cells had fully differentiated.[8]

- An international analysis of several studies found that women who had ever worked 3 hours or more between midnight and 5 a.m., as compared with those who had never done this, had an increased risk for developing breast cancer. This effect was found only in premenopausal women, and was strongest for those premenopausal women who were currently or recently engaged in night shift work. The increased risk was found for development of ER+ tumors, especially those that were also HER2+.[9]

Evidence from studies of changes in ambient environmental light:

- Exposure to ambient artificial light in the bedroom at night (as a result of light pollution in urban areas) can contribute to a disrupted circadian rhythm and can increase the risk of breast cancer.[10],[11]

- In a report from the California Teachers Study, exposure to high levels of outdoor light-at-night (from street lamps, urban lighting, etc.) was associated in an increased risk for developing breast cancer in premenopausal women, especially for those women who are neither overweight or obese.[12]

- Similarly, in a large longitudinal study of nurses’ health, higher levels of residential outdoor light-at-night were associated with increased risk for developing breast cancer in premenopausal women, especially those who have a history (present or past) of smoking cigarettes.[13]

- A study from Spain examined the association between outdoor artificial light-at-night and breast cancer risk. Increased exposures, especially in the blue light spectrum, were associated with higher risk.

- In studies from Korea and Israel looking at regional patterns of ambient light, higher light pollution in both rural and urban areas was associated with increased breast cancer, although no increases in several other cancer rates were seen.[14],[15]

Evidence from studies of disruption to sleep patterns:

- A systematic review of papers exploring possible associations between disturbed sleep patterns and breast cancer risk found mixed results. The researchers used reports of associations in women who have never been engaged in night shift work to develop a physiological model for how sleep disruption, independent of increased light-at-night, could increase risk for breast cancer.[16]

- In a study that followed over 34,000 women for almost 20 years, regularly sleeping less than 8 hours a night was associated with increased risk for developing breast cancer as compared to women who slept 8 hours or longer. This effect was especially strong in post-menopausal women.[17]

Potential mechanisms: Alteration of melatonin secretion patterns, immune system responses:

- Increasing exposure to bright indoor light at night decreases the secretion of melatonin by the pineal gland.[18] Melatonin secretion is important for regulating pituitary and ovarian hormones, as well as for maintaining an overall healthy metabolism.[19] The same genes that mediate the protective effects of melatonin are also thought to be involved in the development of breast cancer.[20] Several studies have found evidence that high levels of melatonin may have a protective effect against breast cancer, while the decrease in melatonin secretion as a result of exposure to light during night shift work is implicated in increasing the risk for breast cancer:

- Increased tumor levels as well as incidence of metastatic cancer in humans were associated in clinical studies with low levels of melatonin.[21]

- In rodent models, higher levels of melatonin have been associated with decreased incidence and size of mammary tumors, and when they do occur, the cancers appear to develop later.[22]

- In human mammary tumors that had been grafted into mice, injections of blood from women that were taken at night (when melatonin is high) decreased proliferation and growth of mammary tumors, as compared to the use of samples collected during the day, when melatonin levels are naturally lower.[23]

- Melatonin cycles in shift workers had different profiles than in non-shift workers. Both the average and the peak levels of melatonin levels were altered in women who worked night shifts. The effect was most pronounced in women who reported that their preferred sleep patterns included going to sleep later in the evening.[24]

- In addition to disruptions in melatonin production, other possible consequences of shift work may be linked to increased cancer rates, and require further study.

What about effects of exposures to light-at-night in women who have been diagnosed with breast cancer?

- A meta-analysis that included 16 studies, collectively including more than 2 million participants, found that night shift work increased all-cause mortality by 25%, although specific results for breast cancer-specific mortality were not available.[29]

- A more recent (2017) study in the Danish nurses’ cohort also demonstrated that evening and night shifts were associated with increased all-cause mortality. In addition, night shift work was associated with increased breast cancer-specific mortality.[30]

- In a study examining possible associations of sleep disturbances with breast cancer characteristics and mortality, chronic sleep disturbance was associated with increased risk of hormone receptor negative (ER-/PR-) breast cancers, but not hormone receptor positive tumors. Chronic sleep disturbance was also associated with higher breast cancer specific mortality in premenopausal, but not postmenopausal, women with the disease.[31]

Who is most likely to be exposed to light-at-night?

Occupations requiring night shift work, particularly overnight shifts, expose employees to light during the night hours, and these occupations may increase individuals’ risk of developing breast cancer. Evidence has been found linking night shift work and increased incidence of cancer in occupations such as nursing and airline work (specifically flight attendants).[32],[33]

Who is most vulnerable to the health effects of light-at-night?

Night shift work may affect individuals’ levels of melatonin differently depending on race and ethnic background.[34] Studies have found that Asian and Asian American women who work night shifts actually have less melatonin suppression than white women.[35] The effects of night shift work may also be related to breast tumor type. One study found that night shift work increased the risk of breast cancer, and specifically increased the likelihood of hormone-receptor-positive pre-menopausal breast cancer.[36]

What are the top tips to avoid exposure?

- If possible, limit shift work to a few years.

- If sleeping during daylight, use blackout curtains or window shades and wear an eye mask to create a totally dark environment.

- Use blackout curtains or window shades to reduce ambient nighttime light pollution, especially in bright urban environments.

- Create a sleeping environment free from electronic lights.

- Support research into the best patterns of shift work.

Updated 2021

[1] Stevens, Richard G. “Working against our endogenous circadian clock: Breast cancer and electric lighting in the modern world.” Mutation Research 680,1-2 (2009): 106-8. doi:10.1016/j.mrgentox.2009.08.004.

[2] Cos, S, and E J Sánchez-Barceló. “Melatonin and mammary pathological growth.” Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology 21, 2 (2000): 133-70. doi:10.1006/frne.1999.0194.

[3] International Agency for Research on Cancer. “IARC Monographs Meeting 124: Night Shift Work (4–11 June 2019), Questions and Answers.” Last modified July 5, 2019. https://www.iarc.fr/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/QA_Monographs_Volume124.pdf.

[4] Slack, Rebecca et al. “Occupational cancer in Britain. Female cancers: breast, cervix and ovary.” British Journal of Cancer 107, 1, 1 (2012): S27-32. doi:10.1038/bjc.2012.115.

[5] Salamanca-Fernández E et al. “Night-shift work and breast and prostate cancer risk: Updating the evidence from epidemiological studies.” Annales del Sistema Sanitario de Navarra 41, 2 (2018): 211–26. doi:10.23938/assn.0307.

[6] Hansen, Johnni, and Richard G Stevens. “Case-control study of shift-work and breast cancer risk in Danish nurses: impact of shift systems.” European Journal of Cancer 48, 11 (2012): 1722-9. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2011.07.005.

[7] McNeely, Eileen et al. “Cancer prevalence among flight attendants compared to the general population.” Environmental Health 17, 1 (2018): 49. doi:10.1186/s12940-018-0396-8.

[8] Menegaux, Florence et al. “Night work and breast cancer: a population-based case-control study in France (the CECILE study).” International Journal of Cancer 132, 4 (2013): 924-31. doi:10.1002/ijc.27669.

[9] Cordina-Duverger, Emilie et al. “Night shift work and breast cancer: a pooled analysis of population-based case-control studies with complete work history.” European Journal of Epidemiology 33, 4 (2018): 369-379. doi:10.1007/s10654-018-0368-x.

[10] Blask, David E et al. “Circadian regulation of molecular, dietary, and metabolic signaling mechanisms of human breast cancer growth by the nocturnal melatonin signal and the consequences of its disruption by light at night.” Journal of Pineal Research 51, 3 (2011): 259-69. doi:10.1111/j.1600-079X.2011.00888.x.

[11] Stevens, Richard G. “Working against our endogenous circadian clock: Breast cancer and electric lighting in the modern world.” Mutation Research 680,1-2 (2009): 106-8. doi:10.1016/j.mrgentox.2009.08.004.

[12] Hurley, Susan et al. “Breast cancer risk and serum levels of per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances: a case-control study nested in the California Teachers Study.” Environmental Health 17, 1 (2018): 83. doi:10.1186/s12940-018-0426-6.

[13] James, Peter et al. “Outdoor Light at Night and Breast Cancer Incidence in the Nurses’ Health Study II.” Environmental Health Perspectives 125, 8 (2017): 087010. doi:10.1289/EHP935.

[14] Kim, Yun Jeong et al. “High prevalence of breast cancer in light polluted areas in urban and rural regions of South Korea: An ecologic study on the treatment prevalence of female cancers based on National Health Insurance data.” Chronobiology International 32, 5 (2015): 657-67. doi:10.3109/07420528.2015.1032413.

[15] Keshet-Sitton, Atalya et al. “Illuminating a Risk for Breast Cancer: A Preliminary Ecological Study on the Association Between Streetlight and Breast Cancer.” Integrative Cancer Therapies 16, 4 (2017): 451-463. doi:10.1177/1534735416678983.

[16] Samuelsson, Laura B et al. “Sleep and circadian disruption and incident breast cancer risk: An evidence-based and theoretical review.” Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 84 (2018): 35-48. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.10.011.

[17] Cao, Jinhong et al. “Sleep duration and risk of breast cancer: The JACC Study.” Breast Cancer Research and Treatment 174, 1 (2019): 219-225. doi:10.1007/s10549-018-4995-4.

[18] Cos, Samuel et al. “Melatonin inhibits the growth of DMBA-induced mammary tumors by decreasing the local biosynthesis of estrogens through the modulation of aromatase activity.” International Journal of Cancer 118, 2 (2006): 274-8. doi:10.1002/ijc.21401.

[19] Cos, S, and E J Sánchez-Barceló. “Melatonin and mammary pathological growth.” Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology 21, 2 (2000): 133-70. doi:10.1006/frne.1999.0194.

[20] Zhu, Yong et al. “Epigenetic impact of long-term shiftwork: pilot evidence from circadian genes and whole-genome methylation analysis.” Chronobiology International 28, 10 (2011): 852-61. doi:10.3109/07420528.2011.618896.

[21] Cos, S, and E J Sánchez-Barceló. “Melatonin and mammary pathological growth.” Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology 21, 2 (2000): 133-70. doi:10.1006/frne.1999.0194.

[22] Cos, S, and E J Sánchez-Barceló. “Melatonin and mammary pathological growth.” Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology 21, 2 (2000): 133-70. doi:10.1006/frne.1999.0194.

[23] Blask, David E et al. “Circadian regulation of molecular, dietary, and metabolic signaling mechanisms of human breast cancer growth by the nocturnal melatonin signal and the consequences of its disruption by light at night.” Journal of Pineal Research 51, 3 (2011): 259-69. doi:10.1111/j.1600-079X.2011.00888.x.

[24] Leung, Michael et al. “Shift Work, Chronotype, and Melatonin Patterns among Female Hospital Employees on Day and Night Shifts.” Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 25, 5 (2016): 830-8. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-1178.

[25] Anjum, B. et al. “Associations of Circadian Disruption of Sleep and Nutritional Factors with Risk of Cancer.” The Open Nutraceuticals Journal 5 (2012): 124-135. doi:10.2174/1876396001205010124.

[26] Aronson, Kristan J et al. “Causes of breast cancer: could work at night really be a cause?” Breast Cancer Management 4 (2015): 125-7. doi:10.2217/bmt.15.4.

[27] Fritschi, L et al. “Hypotheses for mechanisms linking shiftwork and cancer.” Medical Hypotheses 77, 3 (2011): 430-6. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2011.06.002.

[28] Aronson, Kristan J et al. “Causes of breast cancer: could work at night really be a cause?” Breast Cancer Management 4 (2015): 125-7. doi:10.2217/bmt.15.4.

[29] Lin, Xiaoti et al. “Night-shift work increases morbidity of breast cancer and all-cause mortality: a meta-analysis of 16 prospective cohort studies.” Sleep Medicine 16, 11 (2015): 1381-1387. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2015.02.543.

[30] Jørgensen, Jeanette et al. “Shift work and overall and cause-specific mortality in the Danish nurse cohort.” Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health 43, 2 (2016):117–26. doi:10.5271/sjweh.3612.

[31] Vaughn, Caila B et al. “Sleep and Breast Cancer in the Western New York Exposures and Breast Cancer (WEB) Study.” Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine 14, 1 (2018): 81-86. doi:10.5664/jcsm.6886.

[32] Hansen, Johnni, and Richard G Stevens. “Case-control study of shift-work and breast cancer risk in Danish nurses: impact of shift systems.” European Journal of Cancer 48, 11 (2012): 1722-9. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2011.07.005.

[33] He, Chunla et al. “Circadian disrupting exposures and breast cancer risk: a meta-analysis.” International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health 88, 5 (2015): 533-47. doi:10.1007/s00420-014-0986-x.

[34] Pronk, Anjoeka et al. “Night-shift work and breast cancer risk in a cohort of Chinese women.” American Journal of Epidemiology 171, 9 (2010): 953-9. doi:10.1093/aje/kwq029.

[35] Bhatti, Parveen, Dana K Mirick and Scott Davis,. “Racial differences in the association between night shift work and melatonin levels among women.” American Journal of Epidemiology 177, 5 (2013): 388-93. doi:10.1093/aje/kws278.

[36] Papantoniou, Kyriaki et al. “Breast cancer risk and night shift work in a case-control study in a Spanish population.” European Journal of Epidemiology 31, 9 (2016): 867-78. doi:10.1007/s10654-015-0073-y.

[37] National Toxicology Program, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, Research Triangle Park, NC, USA. Public Health Service U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. “Running title: Night Shift Work and Light at Night and Cancer.” National Toxicology Program Cancer Hazard Assessment Report on Night Shift Work and Light at Night (April 2021). https://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/ntp/results/pubs/cancer_assessment/lanfinal20210400_508.pdf.

Types: Article