Dichloro-Diphenyl-Trichloroethane (DDT)

At a Glance

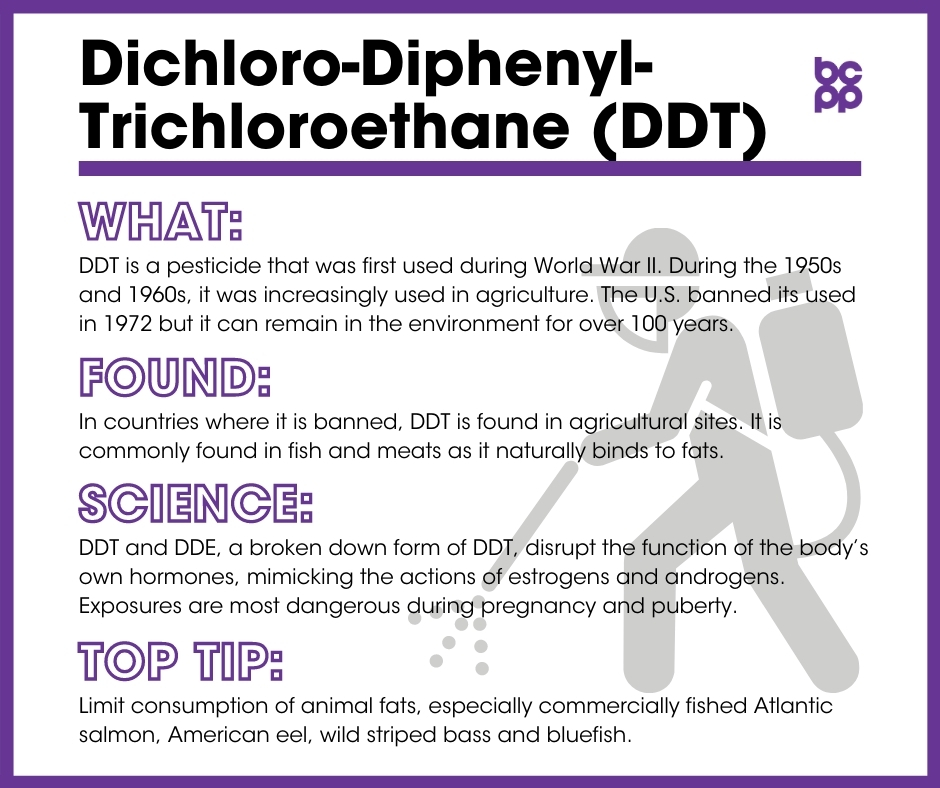

Dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane (DDT) is a pesticide that was first used in World War II in order to control insects that carry human diseases such as malaria. It is also effective against insects such as the gypsy moth, which attack crops. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, DDT was used increasingly in agriculture.

DDT and its major metabolite, or breakdown product, dichloro-diphenyldichloro-ethane (DDE), can be found in the blood samples of a majority of people around the world.

DDT and DDE disrupt the function of the body’s own hormones, with DDT mimicking the actions of estrogen, and DDE mimicking androgens. DDT and DDE cross the placenta. Prenatal exposure appears to increase risk of breast cancer in adulthood. Some of the highest concentrations of DDT and DDE in humans have been found in breast milk, which also makes breastfeeding infants at risk of DDT and DDE exposure.

The disastrous effects of DDT on animal reproduction and wildlife following widespread use in World War II and in the 1950-1960s led to its ban in most, but not all, countries.

What are DDT and DDE?

DDT is a pesticide that was first used in World War II to control insects that carry human diseases such as malaria. It is also effective against insects such as the gypsy moth, which attack crops. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, DDT was used increasingly in agriculture.

DDT breaks down into several metabolites (breakdown products). The most common of these is DDE.[1] Though the pesticide is not currently used widely in the U.S. and Europe, it still is used (often illegally) in Africa and, especially, India.[2] It persists in human and animal tissues and soil for long periods of time. As a result, it is an ongoing concern for humans. DDT and DDE have long half-lives of about ten and five years, respectively. It is possible that the complete degradation of all existing DDT and DDE could take over 100 years.[3],[4]

Where are DDT and DDE found?

Following World War II, DDT was mainly used as an insecticide on crops. It was banned from use in the United States in 1972. It is, however, still used to kill mosquitos in malaria-prone areas such as some sub-Saharan African countries as well as India and North Korea.[5]

In countries where DDT is banned, it is found chiefly in agricultural sites.[6] In these agricultural communities, legacy DDT can be found in low concentrations in the air and drinking water.[7],[8] All other communities are primarily exposed to DDT and DDE through food. These chemicals are commonly found in foods that contain animal fats where DDT accumulates, such as meats and fish.[9]

What evidence links DDT and DDE to breast cancer?

DDT and DDE disrupt the function of the body’s own hormones, with DDT mimicking the actions of estrogen, and DDE mimicking androgens.[10]

The most important and comprehensive set of studies linking subsequent development of breast cancer and exposures to DDT, especially during early development and pregnancy, come from the Child Health and Development Study (CHDS). The CHDS is a large, long-term study that originally enrolled women in Alameda County, California between 1959 and 1967, very early during their pregnancies. In the first few days after the women gave birth, blood samples were taken from the mothers and stored. These blood samples have been tested for many chemicals, including DDT and DDE. Over the past 60 years or so, scientists have followed the health of both the mothers from this study as well as their daughters who are now approaching, on average, their mid-fifties. Several papers have reported important findings from the CHDS.[11],[12],[13]

- Fetal exposures of the CHDS daughters to DDT and DDE were linked to an increased risk for breast cancer later in life. Daughters whose mothers had high levels of DDT or DDE in their blood around the time of giving birth were four times as likely to have developed breast cancer 54 years later.[14]

- Young CHDS mothers who were exposed to high levels of DDT prior to the age of 14 were five times as likely to experience breast cancer as women who were not exposed, or first became exposed after the age of 14. The risk was more pronounced the younger the child was in 1945, the year widespread spraying of DDT began. Girls under the age of 4 in 1945 whose mothers had high levels of blood DDT when they gave birth had an over 10-fold increase in breast cancer risk by age 50, compared with those whose mothers had low levels of blood DDT. Other maternal health factors, like history of their own breast cancer, body weight, age, etc., were not linked with risk of daughters developing the disease.[15]

- In follow-up studies, CHDS scientists reported that while DDT levels in mothers’ blood samples were inversely related to body mass index (BMI, a measure of relative obesity) in healthy daughters, this was not true in daughters who developed breast cancer before the age of 50. This suggests an abnormal decoupling of the relationship between the endocrine disruptor, DDT, and fat tissue metabolism.[16] Another, much smaller study, did find a positive relationship between DDE levels and BMI in women who had been diagnosed with breast cancer. This report also found higher levels in blood of women diagnosed with Stage I versus Stage II cancer, and with ER+/ER2-, as compared to any HER2+, tumors.[17]

- In another follow-up study of the CHDS cohort, in daughters who had not developed breast cancer before the age of 52, high levels of serum maternal DDT were associated with increased breast density.[18] Higher breast density is a known risk for developing breast cancer in both pre- and post-menopausal women.[19]

Results of many other recent studies, from both the U.S. and internationally, have supported the results from the CHDS reports. In a 2019 report from Iran, higher blood levels of DDT and DDE were each associated with increases in both benign and malignant breast cancer, as compared to women with low blood levels of these chemicals.[20] Similarly a Chinese study found higher levels of DDT and DDE in women who had been diagnosed with breast cancer than in healthy controls, although there was no relationship between the pesticides levels and characteristics of the women’s tumors.[21] Both of these studies measured DDT/DDE levels around the time of diagnosis, but in areas where women would have been exposed to the chemicals throughout their lifetimes.

One study from Taiwan did look at age at exposure, although the data were gathered at the township level, i.e., how many times were hometowns sprayed when the women were young girls versus breast cancer incidence for nine birth cohorts from almost 350 towns. Results indicated that DDT exposure before the age of five years old was associated with an increased risk of cancer, and the results were strengthened as the number of DDT exposures increased.[22]

Another study from Long Island followed women who may have followed DDT fogger trucks before 1972. Researchers looked at DDT levels in the late 1990s and found that while there was no overall increase in breast cancer incidence in women who reported having followed fogger trucks as children, there was an increase in ER+/PR+ cancers.[23]

Other studies that examined adult exposures to DDT have been inconclusive, [24],[25],[26] but these studies have looked at blood or urine levels of the chemical at the time of diagnosis of breast cancer, not earlier in life. As indicated above, what may matter most is high levels of DDT exposure during childhood through early adolescence.

In rodents, the cancer-inducing capabilities of DDT are well documented. For example, rats that were fed DDT were much more likely to develop mammary gland tumors than rats that did not consume DDT.[27] Animal and cell culture studies examining the mechanisms by which DDT and DDE influence the risk of breast cancer indicate that the chemicals are weak estrogen mimics, working by activating both the traditional estrogen receptor (ER) as well as other estrogen-regulated pathways in breast and other cells.[28]

What are the links between DDT/DDE exposures and survival after a breast cancer diagnosis?

Two 2016 studies have looked at possible associations between DDT and DDE levels measured just after diagnosis in women with breast cancer and survival 5, 15 or 20 years after diagnosis. One found that women from Long Island with the highest levels of blood DDT at five years post-diagnosis had more than twice the rates of both all-cause mortality (cancer, cardiovascular disease, etc.) as well as breast cancer-specific mortality. At 15 years post-diagnosis, women with the middle third levels of DDT had had increased rates of both all-cause and breast cancer specific mortality.[29]

In a study from North Carolina, with significant numbers of both Black and White women who had been diagnosed with breast cancer and then followed for, on average, just over 20 years, increased levels of both DDT and DDE at time of diagnosis were associated with higher rates of all-cause mortality. Higher levels of serum DDE were also associated with increased breast cancer specific mortality, and this result was stronger in Black than White women, and in women diagnosed with ER-, as compared with ER+, tumors.[30]

Who is most likely to be exposed to DDT and DDE?

Virtually everyone is exposed to residual DDT and DDE, which remains in soil, plants and the food chain.[31]

Who is most vulnerable to the health effects of DDT and DDE?

DDT exposures seem to have the most profound consequences when they occur during critical periods of breast development, including prenatal development, childhood, puberty and pregnancy.[32],[33]

DDT and DDE cross the placenta, and prenatal exposure appears to increase risk of breast cancer in adulthood.[34] Some of the highest concentrations of DDT and DDE in humans have been found in breast milk, which also makes breastfeeding infants at risk of DDT and DDE exposure.[35],[36] In general, however, the benefits of breastfeeding still outweigh the risks.

Agricultural workers are also at an increased risk of being exposed to DDT. This is because DDT often exists residually in soil as a result its wide use throughout the 1950s and ’60s.[37]

What are the top tips to avoid exposure?

- Wild fish often have high levels of pesticides, including DDT. Commercial fish that could contain dangerous levels of DDT include Atlantic salmon, American eel, wild striped bass and bluefish.[38]

- Limiting the consumption of animal fat can also reduce the risk of excessive exposure to DDT and DDE, as it is stored in fat.[39]

Updated 2021

[1] Parada, Humberto Jr et al. “Organochlorine insecticides DDT and chlordane in relation to survival following breast cancer.” International Journal of Cancer 138,3 (2016): 565-75. doi:10.1002/ijc.29806.

[2] van den Berg, Henk et al. “Global trends in the production and use of DDT for control of malaria and other vector-borne diseases.” Malaria Journal 16,1 (2017): 401. doi:10.1186/s12936-017-2050-2.

[3] Ingber Susan Z et al. “DDT/DDE and breast cancer: a meta-analysis.” Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology 67, 3(2013): 421-433. doi:10.1016/j.yrtph.2013.08.021.

[4] National Pesticide Information Center. “DDT (General Fact Sheet).” Last modified 1999. http://npic.orst.edu/factsheets/ddtgen.pdf.

[5] Cone, Marla. “Should DDT be used to combat Malaria?” Scientific American May 4, 2009. http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/ddt-use-to-combat-malaria/.

[6] White, Alexandra J et al. “Exposure to fogger trucks and breast cancer incidence in the Long Island Breast Cancer Study Project: a case–control study.” Environmental Health 12, 24 (2013). doi:10.1186/1476-069X-12-24.

[7] Frontline. “Primer: Legacy Pollutants.” Last modified April 21, 2009. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/poisonedwaters/themes/legacy.html.

[8] World Health Organization. “DDT and Its Derivatives in Drinking Water: Background documents for development of WHO Guidelines for Drinking-water Quality.” Last modified 2004. http://www.who.int/water_sanitation_health/dwq/chemicals/ddt.pdf.

[9] World Health Organization. “DDT and Its Derivatives in Drinking Water: Background documents for development of WHO Guidelines for Drinking-water Quality.” Last modified 2004. http://www.who.int/water_sanitation_health/dwq/chemicals/ddt.pdf.

[10] Pestana, Diogo et al. “Effects of environmental organochlorine pesticides on human breast cancer: putative involvement on invasive cell ability.” Environmental Toxicology 30, 2 (2015): 168-76. doi:10.1002/tox.21882.

[11] Cohn, Barbara A et al. “DDT Exposure in Utero and Breast Cancer.” Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 100, 8 (2015): 2865-72. doi:10.1210/jc.2015-1841.

[12] Cohn, Barbara A et al. “DDT and breast cancer in young women: new data on the significance of age at exposure.” Environmental Health Perspectives 115, 10 (2007): 1406-14. doi:10.1289/ehp.10260.

[13] Soto, Ana M, and Carlos Sonnenschein. “Endocrine disruptors: DDT, endocrine disruption and breast cancer.” Nature Reviews Endocrinology 11, 9 (2015): 507-8. doi:10.1038/nrendo.2015.125.

[14] Cohn, Barbara A et al. “DDT Exposure in Utero and Breast Cancer.” Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 100, 8 (2015): 2865-72. doi:10.1210/jc.2015-1841.

[15] Cohn, Barbara A et al. “DDT and breast cancer in young women: new data on the significance of age at exposure.” Environmental Health Perspectives 115, 10 (2007): 1406-14. doi:10.1289/ehp.10260.

[16] Cohn, Barbara A, Piera M Cirillo and Mary Beth Terry. “DDT and Breast Cancer: Prospective Study of Induction Time and Susceptibility Windows.” Journal of the National Cancer Institute 111, 8 (2019): 803-810. doi:10.1093/jnci/djy198.

[17] Ellsworth, Rachel E et al. “Organochlorine pesticide residues in human breast tissue and their relationships with clinical and pathological characteristics of breast cancer.” Environmental Toxicology (2018). doi:10.1002/tox.22573.

[18] Krigbaum, Nickilou Y et al. “In utero DDT exposure and breast density before age 50.” Reproductive Toxicology 92 (2020): 85-90. doi:10.1016/j.reprotox.2019.11.002.

[19] Byrne, C et al. “Mammographic features and breast cancer risk: effects with time, age, and menopause status.” Journal of the National Cancer Institute 87,21 (1995): 1622-9. doi:10.1093/jnci/87.21.1622.

[20] Paydar, Parisa et al. “Serum levels of Organochlorine Pesticides and Breast Cancer Risk in Iranian Women.” Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 77 (2019): 480–489. doi:10.1007/s00244-019-00648-3.

[21] He, Ting-Ting et al. “Organochlorine pesticides accumulation and breast cancer: A hospital-based case-control study.” Tumour Biology : the journal of the International Society for Oncodevelopmental Biology and Medicine 39,5 (2017): 1010428317699114. doi:10.1177/1010428317699114.

[22] Chang, Simon et al. “DDT exposure in early childhood and female breast cancer: Evidence from an ecological study in Taiwan.” Environment international 121, 2 (2018): 1106-1112. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2018.10.023.

[23] White, Alexandra J et al. “Exposure to fogger trucks and breast cancer incidence in the Long Island Breast Cancer Study Project: a case–control study.” Environmental Health 12, 24 (2013). doi:10.1186/1476-069X-12-24.

[24] Ingber Susan Z et al. “DDT/DDE and breast cancer: a meta-analysis.” Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology 67, 3(2013): 421-433. doi:10.1016/j.yrtph.2013.08.021.

[25] White, Alexandra J et al. “Exposure to fogger trucks and breast cancer incidence in the Long Island Breast Cancer Study Project: a case–control study.” Environmental Health 12, 24 (2013). doi:10.1186/1476-069X-12-24.

[26] Park, Jae-Hong et al. “Exposure to Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane and the Risk of Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis.” Osong Public Health and Research Perspectives 5, 2 (2014): 77-84. doi:10.1016/j.phrp.2014.02.001.

[27] Scribner, John D. and Karle Mottet. “DDT acceleration of mammary gland tumors induced in the male Sprague-Dawley rat by 2-acetamidophenanthrene.” Carcinogenesis 2, 12 (1981): 1235-1239. doi:10.1093/carcin/2.12.1235.

[28] Vandenberg, Laura N et al. “Agrochemicals with estrogenic endocrine disrupting properties: Lessons Learned?.” Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology 518 (2020): 110860. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2020.110860.

[29] Parada, Humberto Jr et al. “Organochlorine insecticides DDT and chlordane in relation to survival following breast cancer.” International Journal of Cancer 138,3 (2016): 565-75. doi:10.1002/ijc.29806.

[30] Parada, Humberto Jr et al. “Plasma levels of dichlorodiphenyldichloroethene (DDE) and dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) and survival following breast cancer in the Carolina Breast Cancer Study.” Environment International 125 (2019): 161-171. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2019.01.032.

[31] Tang, Mengling et al. “Assessing the underlying breast cancer risk of Chinese females contributed by dietary intake of residual DDT from agricultural soils.” Environment International 73 (2014): 208-15. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2014.08.001.

[32] Soto, Ana M, and Carlos Sonnenschein. “Endocrine disruptors: DDT, endocrine disruption and breast cancer.” Nature Reviews Endocrinology 11, 9 (2015): 507-8. doi:10.1038/nrendo.2015.125.

[33] Cohn, Barbara A et al. “DDT Exposure in Utero and Breast Cancer.” Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 100, 8 (2015): 2865-72. doi:10.1210/jc.2015-1841.

[34] Park, Jae-Hong et al. “Exposure to Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane and the Risk of Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis.” Osong Public Health and Research Perspectives 5, 2 (2014): 77-84. doi:10.1016/j.phrp.2014.02.001.

[35] National Pesticide Information Center. “DDT (General Fact Sheet).” Last modified 1999. http://npic.orst.edu/factsheets/ddtgen.pdf.

[36] Cohn, Barbara A et al. “DDT Exposure in Utero and Breast Cancer.” Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 100, 8 (2015): 2865-72. doi:10.1210/jc.2015-1841.

[37] Tang, Mengling et al. “Assessing the underlying breast cancer risk of Chinese females contributed by dietary intake of residual DDT from agricultural soils.” Environment International 73 (2014): 208-15. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2014.08.001.

[38] Toxic-Free Future. “PCBs and DDT.” Accessed October 28, 2020. https://toxicfreefuture.org/key-issues/chemicals-of-concern/pcbs-and-ddt/.

[39] Toxic-Free Future. “PCBs and DDT.” Accessed October 28, 2020. https://toxicfreefuture.org/key-issues/chemicals-of-concern/pcbs-and-ddt/.