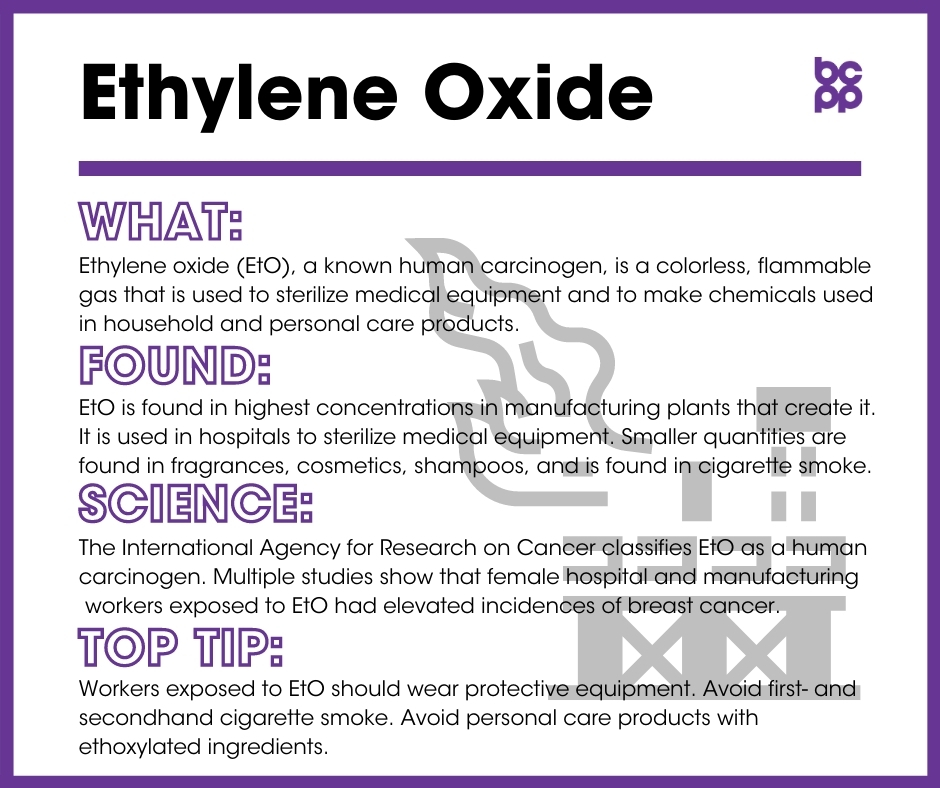

Ethylene Oxide

At a Glance

Ethylene oxide (EtO), a known human carcinogen with strong evidence linking exposures to EtO to the development of lymphoma and breast cancer. EtO is a colorless, flammable gas that is used to sterilize medical equipment and to make chemicals used in household and personal care products. After these processes, traces of EtO are sometimes left behind.

During the 1980s, it is estimated that more than 270,000 U.S. workers were exposed to the chemical every year. The use of EtO has since decreased in the United States, although it is still used.

What is ethylene oxide?

Ethylene oxide is a fumigant used to sterilize surgical equipment. It is also used in a process called ethoxylation, in which ethylene oxide is added to ingredients to make them less irritating. Ethoxylated products are widely used in personal care and household cleaning products.[1] The majority of ethylene oxide is produced in order to manufacture other chemicals.[2]

When in contact with ethylene oxide, humans absorb it through their skin or breathe it in.[3] Once it enters the bloodstream, EtO exhibits endocrine-disrupting capabilities.[4] It also causes direct damage to DNA.[5]

Where is ethylene oxide found?

Ethylene oxide is found in highest concentrations in the manufacturing plants that create it. It is also prevalent in hospitals, where it is used to sterilize medical equipment.[6] People living near industrial facilities that emit EtO may have significantly elevated levels of the chemical.[7]

Smaller quantities of EtO can be found in fragrances, shampoos and other cosmetic items as well as cigarette smoke.[8],[9]

What evidence links ethylene oxide to breast cancer?

The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classifies ethylene oxide as a known human carcinogen.[10] The U.S. EPA Carcinogenicity Assessment also found EtO exposures to be carcinogenic, with the strongest evidence linking EtO exposures to development of lymphoma and breast cancer.[11] These determinations reflect the assessment of the combined results of epidemiological, lab animal and mechanistic studies on the associations between EtO exposure and risk of breast cancer development.

Female Swedish, Hungarian and American hospital and manufacturing workers who were exposed to varying levels of ethylene oxide had elevated incidences of breast cancer.[12],[13],[14],[15]

A U.S. study examined mortality rates from various cancers for workers exposed to EtO across several sterilization facilities and found increased exposures were associated with higher mortality from hematopoietic (lymphoma, leukemia) and breast cancers.[16] A 2020 reanalysis of those results found even stronger relationships between cumulative EtO exposures and breast cancer specific mortality rates when employment duration was taken into account, recognizing that women who were more sensitive to the irritant qualities of EtO exposures would leave their jobs sooner and would not have been counted in the original mortality data analyses.[17]

An ecological study in Illinois examined possible links between breast cancer rates at the county level and several toxic chemicals measured in air and also reported at the county level. Higher air levels of ethylene oxide were associated with increased risk for breast cancer.[18]

An analysis of blood levels of EtO from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) did not find any relationship between EtO levels and risk of having been diagnosed with breast cancer in data pooled across women from all ages from 20 years on. But not only was there no age breakdown of these results, there was no sorting by occupational or other possible EtO exposure sources beyond smoking history.[19]

Two recent narrowly conceived reviews of the epidemiological data linking breast cancer and EtO exposures concluded that the evidence was insufficient to warrant conclusions that there was a significant link. Both papers were conducted by researchers employed by chemical industry supported companies. [20],[21]

Ethylene oxide interferes with biological processes that build proteins and replicate DNA.[22] EtO does this by binding to DNA and causing mutations that can stop cells from making proteins. Most cells have the ability to recognize and repair unexpected changes that chemicals can cause, but others replicate too quickly to do so. Epithelial cells outline blood vessels, and stromal cells make up tissues that support the structure of organs. These are examples of quickly replicating cells that sometimes miss the changes that EtO makes.[23] These sorts of alterations in breast epithelial and stromal cells can cause carcinomas and sarcomas respectively.[24],[25]

There is also extensive evidence of carcinogenicity in rats and mice. After inhaling ethylene oxide, animals presented with mammary tumors. The tumor incidence increased when animals were exposed to higher concentrations of EtO.[26],[27],[28]

A study conducted on human cells in vitro showed that even small levels of exposure to EtO caused DNA damage in epithelial breast cells. This damage worsened as cells were treated with higher concentrations, demonstrating the sensitivity of breast epithelial cells to EtO.[29]

Who is most likely to be exposed to ethylene oxide?

- Hospital personnel who sanitize surgical instruments using ethylene oxide.[30]

- People who work in ethylene oxide manufacturing plants and those who live in surrounding communities.[31]

Who is most vulnerable to the health effects of ethylene oxide?

People who work in close contact with ethylene oxide are most vulnerable to its health effects. Exposure to higher concentrations of EtO increase these risks.[32]

What are the top tips to avoid exposure?

- Workers who are exposed to ethylene oxide should wear protective eye gear and clothing, and should use respirators when exposed.[33]

- First- and secondhand cigarette smoke should be avoided.[34]

- Avoid personal care products with ethoxylated ingredients. These show up on the label with the suffix –eth (ceteareth, laureth, steareth, etc.), the abbreviations PPG or PEG, or polysorbate.

Other names for ethylene oxide: Dihydrooxirene; dimethylene oxide; EO; 1,2-epoxyethane; epoxyethane ethene oxide; EtO; ETO; oxaxyclopropane; oxane; oxidoethane.[35]

Updated 2021

[1] Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR). Toxicological Profile for Ethylene Oxide (Draft for Public Comment). Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, 2020. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/tp.asp?id=734&tid=133.

[2] Norman SA et al. “Cancer incidence in a group of workers potentially exposed to ethylene oxide.” International Journal of Epidemiology 24, 2(1995): 276-84.

[3] World Health Organization. “Concise International Chemical Assessment Document 54: Ethylene Oxide.” Last modified 2003. http://www.who.int/ipcs/publications/cicad/en/cicad54.pdf.

[4] Norman SA et al. “Cancer incidence in a group of workers potentially exposed to ethylene oxide.” International Journal of Epidemiology 24, 2(1995): 276-84.

[5] World Health Organization. “Concise International Chemical Assessment Document 54: Ethylene Oxide.” Last modified 2003. http://www.who.int/ipcs/publications/cicad/en/cicad54.pdf.

[6] IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. “1,3-Butadiene, Ethylene Oxide and Vinyl Halides (Vinyl Fluoride, Vinyl Chloride and Vinyl Bromide).” Lyon (FR): International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2008. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK321405/.

[7] Szwiec, Emily et al. “Levels of Ethylene Oxide Biomarker in an Exposed Residential Community.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17,22 (2020): 8646. doi:10.3390/ijerph17228646.

[8] Konduracka, Ewa, Krzysztof Krzemieniecki and Grzegorz Gajos. “Relationship between everyday use cosmetics and female breast cancer.” Polskie Archiwum Medycyny Wewnetrznej 124, 5 (2014): 264-9. doi:10.20452/pamw.2257.

[9] Fennell, Timothy R. et al. “Hemoglobin Adducts from Acrylonitrile and Ethylene Oxide in Cigarette Smokers: Effects of Glutathione S-Transferase T1-Null and M1-Null Genotypes.” Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers 9, 7 (2000): 705-712.

[10] IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans Volume 100F. “Chemical Agents and Related Occupations.” Last modified 2012. http://monographs.iarc.fr/ENG/Monographs/vol100F/mono100F-28.pdf.

[11] Jinot, Jennifer et al. “Carcinogenicity of ethylene oxide: key findings and scientific issues.” Toxicology Mechanisms and Methods 28,5 (2018): 386-396. doi:10.1080/15376516.2017.1414343.

[12] Mikoczy, Zoli et al. “Cancer incidence and mortality in Swedish sterilant workers exposed to ethylene oxide: updated cohort study findings 1972-2006.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 8, 6 (2011): 2009-19. doi:10.3390/ijerph8062009.

[13] Norman SA et al. “Cancer incidence in a group of workers potentially exposed to ethylene oxide.” International Journal of Epidemiology 24, 2(1995): 276-84.

[14] Steenland, Kyle et al. “Ethylene oxide and breast cancer incidence in a cohort study of 7576 women (United States).” Cancer Causes & Control 14, 6 (2003): 531-9. doi:10.1023/a:1024891529592.

[15] Tompa, Anna, Jenô Major and Mátyás G Jakab. “Is Breast Cancer Cluster Influenced by Environmental and Occupational Factors Among Hospital Nurses in Hungary?” Pathology Oncology Research 5, 2 (1999): 117-121. doi:10.1053.paor.1999.0182.

[16] Steenland, Kyle et al. “Ethylene oxide and breast cancer incidence in a cohort study of 7576 women (United States).” Cancer Causes & Control 14, 6 (2003): 531-9. doi:10.1023/a:1024891529592.

[17] Park, Robert M. “Associations between exposure to ethylene oxide, job termination, and cause-specific mortality risk.” American Journal of Industrial Medicine 63,7 (2020): 577-588. doi:10.1002/ajim.23115.

[18] Chen X. “A temporal analysis of the association between breast cancer and socioeconomic and environmental factors.” GeoJournal 83 (2018): 1239–56. doi:10.1007/s10708-017-9824-5.

[19] Jain, Ram B. “Associations between observed concentrations of ethylene oxide in whole blood and smoking, exposure to environmental tobacco smoke, and cancers including breast cancer: data for US children, adolescents, and adults.” Environmental Science and Pollution Research International 27,17 (2020): 20912-20919. doi:10.1007/s11356-020-08564-z.

[20] Vincent, Melissa J et al. “Ethylene Oxide: Cancer Evidence Integration and Dose-Response Implications.” Dose-Response: A Publication of International Hormesis Society 17,4 (2019). doi:10.1177/1559325819888317.

[21] Marsh, Gary M et al. “Ethylene oxide and risk of lympho-hematopoietic cancer and breast cancer: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis.” International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health 92,7 (2019): 919-939. doi:10.1007/s00420-019-01438-z.

[22] World Health Organization. “Concise International Chemical Assessment Document 54: Ethylene Oxide.” Last modified 2003. http://www.who.int/ipcs/publications/cicad/en/cicad54.pdf.

[23] IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. “1,3-Butadiene, Ethylene Oxide and Vinyl Halides (Vinyl Fluoride, Vinyl Chloride and Vinyl Bromide).” Lyon (FR): International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2008. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK321405/.

[24] Johns Hopkins University. “Types of Breast Cancers: Histologic examples of in situ & invasive carcinomas of the breast.” Accessed October 29, 2020. http://pathology.jhu.edu/breast/types.php.

[25] Ádám, Balázs, Helga Bárdos and Róza Ádány. “Increased genotoxic susceptibility of breast epithelial cells to ethylene oxide.” Mutation Research/Genetic Toxicology and Environmental Mutagenesis 585, 1–2 (2005): 120-126. doi:10.1016/j.mrgentox.2005.04.009.

[26] National Center for Environmental Assessment, Office of Research and Development, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. “Evaluation of the Inhalation Carcinogenicity of Ethylene Oxide: In Support of Summary Information on the Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS).” August 2014. https://yosemite.epa.gov/sab/sabproduct.nsf/fedrgstr_activites/82E68A48EE8ED66685257BA600556607/$File/CARCINOGENICITY-OF-ETO-FOR-SAB-CAAC-REVIEW.PDF.

[27] Rudel, Ruthann A et al. “Chemicals causing mammary gland tumors in animals signal new directions for epidemiology, chemicals testing, and risk assessment for breast cancer prevention.” Cancer 109,12 (2007): 2635-66. doi:10.1002/cncr.22653.

[28] Houle, Christopher D et al. “Frequent p53 and H-ras mutations in benzene- and ethylene oxide-induced mammary gland carcinomas from B6C3F1 mice.” Toxicologic Pathology 34, 6 (2006): 752-62. doi:10.1080/01926230600935912.

[29] Ádám, Balázs, Helga Bárdos and Róza Ádány. “Increased genotoxic susceptibility of breast epithelial cells to ethylene oxide.” Mutation Research/Genetic Toxicology and Environmental Mutagenesis 585, 1–2 (2005): 120-126. doi:10.1016/j.mrgentox.2005.04.009.

[30] IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. “1,3-Butadiene, Ethylene Oxide and Vinyl Halides (Vinyl Fluoride, Vinyl Chloride and Vinyl Bromide).” Lyon (FR): International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2008. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK321405/.

[31] IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. “1,3-Butadiene, Ethylene Oxide and Vinyl Halides (Vinyl Fluoride, Vinyl Chloride and Vinyl Bromide).” Lyon (FR): International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2008. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK321405/.

[32] Steenland, Kyle et al. “Ethylene oxide and breast cancer incidence in a cohort study of 7576 women (United States).” Cancer Causes & Control 14, 6 (2003): 531-9. doi:10.1023/a:1024891529592.

[33] U.S. Department of Labor. “OSHA Fact Sheet: Ethylene Oxide.” Last modified 2002. https://www.osha.gov/OshDoc/data_General_Facts/ethylene-oxide-factsheet.pdf.

[34] Fennell, Timothy R. et al. “Hemoglobin Adducts from Acrylonitrile and Ethylene Oxide in Cigarette Smokers: Effects of Glutathione S-Transferase T1-Null and M1-Null Genotypes.” Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers 9, 7 (2000): 705-712.

[35] Steenland, Kyle et al. “Ethylene oxide and breast cancer incidence in a cohort study of 7576 women (United States).” Cancer Causes & Control 14, 6 (2003): 531-9. doi:10.1023/a:1024891529592.

Types: Article