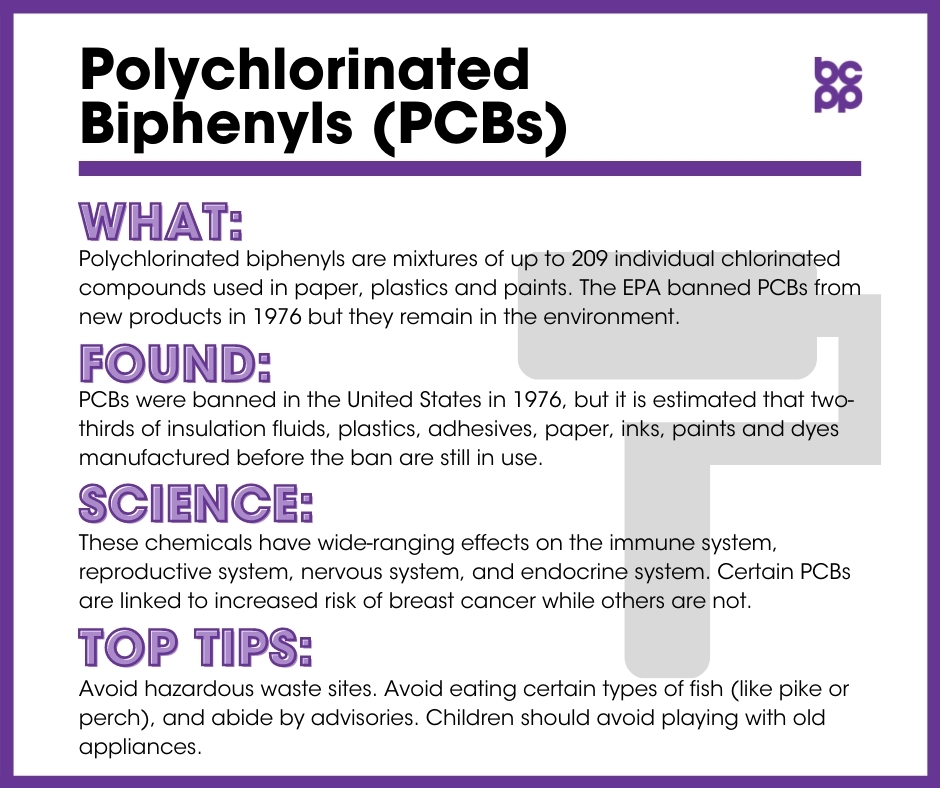

Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs)

At a Glance

PCBs are classified as a probable carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) and a reasonably anticipated carcinogen by the National Toxicology Program (NTP).

The EPA banned PCBs from new products in 1976. Due to their persistence in the environment, they are still found in soil, riverbeds and dust particulates in homes. They also remain in products manufactured prior to the ban such as paper, plastics and paints.

These chemicals have wide-ranging effects on the immune system, reproductive system, nervous system and endocrine system. Certain individual PCBs are linked to increased risk of breast cancer, while others are not because of the differing individual compounds’ effects on endocrine and other biological systems.

What are PCBs?

Polychlorinated biphenyls are mixtures of up to 209 individual chlorinated compounds. There are no known natural sources of PCBs. They are oily liquids or solids that range from colorless to light yellow.[1]

Individual PCBs are classified into three types based on their cellular effects.

- Group I PCBs: Estrogenic

- Group II PCBs: Anti-estrogenic

- Group III PCBs: Not hormonally active, but can stimulate the enzyme systems of animals, including humans, in a manner similar to certain drugs (such as phenobarbital) and other toxic chemicals[2],[3]

Where are PCBs found?

PCBs were banned in the United States in 1976, but it is estimated that two-thirds of insulation fluids, plastics, adhesives, paper, inks, paints and dyes manufactured before the ban are still in use. PCBs are found in the air, in aquifers and in rivers, where they accumulate in the sediment but then are re-dissolved into the water, where they contaminate and bioaccumulate across the food chain.[4],[5]

What evidence links PCBs to breast cancer?

Levels of PCBs were high before being banned in the United States. Their presence in the environment and in human tissues has decreased slowly over the past decades.[6],[7]

- Several epidemiological studies have found that women who regularly ate PCB-contaminated pike or perch had higher risk for breast cancer than women who never ate these fish.[8]

- PCB levels in neonatal cord serum correlate with the distance a mother lives from a toxic waste site. It was found that levels dropped after site cleanup.[9] In the same study, exposure levels were high in childhood and young adulthood among women who were later diagnosed with breast cancer.[10]

- A recent meta-analysis demonstrated that there was no relationship between breast cancer and exposures to Group I PCBs, but there was a significantly increased risk of breast cancer with exposures to either Group II or Group III PCBs.[11]

- A study in France examined levels of PCB-153, an estrogenic (Group I) PCB, in blood samples from women at the time of breast cancer diagnosis and compared these levels to women without the disease. The researchers applied a mathematical model to estimate PCB-153 levels at the time of adolescence, based upon the rate that PBC-153 is broken down. There was no association with risk for breast cancer and PCB-153 levels at the time of diagnosis, although higher estimated levels in adolescence were associated with a decreased risk for later developing the disease.[12]

- A study from China examined PCB levels in breast fat tissue from women who underwent diagnostic surgery to remove breast lumps. Higher total PCB levels were associated with higher clinical stage of breast cancer and greater expression of the estrogen receptor.[13]

- PCB metabolites (breakdown products) may alter the expression of genes that affect hormone production, leading to hormone disruption.[14]

- In a study examining occupational exposures to PCBs in electrical capacitor production workers and later breast cancer incidence, no overall relationship between exposure levels or duration and disease incidence was observed for female workers in general. For non-white women in this industry, however, a significant relationship was found between incidence of breast cancer and exposure to PCBs at a younger age, as well as higher cumulative exposures.[15]

Some studies have found no link between PCBs and breast cancer.[16]

- A 2009 review of the literature concluded that overall PCBs, as a class, were not associated with increased risk for breast cancer.[17]

What about effects of exposures to PCBs in women who have been diagnosed with breast cancer?

- PCBs may be linked to breast cancer recurrence among women with non-metastatic breast cancer. One study found that women with the highest levels of total PCBs, and PCBs in their fat tissues, were almost three times as likely to have recurrent breast cancer as women with lower levels.[18]

Who is most likely to be exposed to PCBs?

For many, the most likely exposure to PCBs is through food contaminated as a result of legacy PCBs in the environment. Meat and dairy products, as well as fish caught in contaminated lakes or rivers, are the most likely to contain PCBs. Workplace exposures may occur during repair of PCB transformers; through accidents, fires or spills involving transformers, fluorescent lights, and other old electrical devices; and during the disposal of PCB materials.[19]

Who is most vulnerable to the health effects of PCBs?

Women with a particular variant of the CYP1A1 gene, involved in metabolism, may be more vulnerable to high exposures to PCBs.[20]

What are the top tips to avoid exposure?

- Avoid hazardous waste sites.

- Avoid eating certain types of fish, such as pike or perch, and abide by advisories.

- Children should avoid playing with old appliances.

- More recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control are available here.

Updated 2019

[2] Wolff, M S et al. “Proposed PCB congener groupings for epidemiological studies.” Environmental Health Perspectives 105, 1 (1997): 13-4. doi:10.1289/ehp.9710513.

[3] Zhang, Jingwen et al. “Environmental Polychlorinated Biphenyl Exposure and Breast Cancer Risk: A Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies.” PloS One 10, 11 (2015): e0142513. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0142513.

[4] Environental Protection Agency. “Learn about Polychlorinated Biphenyls.” Last modified February 6, 2020. Available at: https://www.epa.gov/pcbs/learn-about-polychlorinated-biphenyls-pcbs.

[5] Martinez, Andres et al. “Polychlorinated biphenyl congeners in sediment cores from the Upper Mississippi River.” Chemosphere 144 (2016): 1943-9. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2015.10.090.

[6] Shunthirasingham, Chubashini et al. “Atmospheric concentrations and loadings of organochlorine pesticides and polychlorinated biphenyls in the Canadian Great Lakes Basin (GLB): Spatial and temporal analysis (1992-2012).” Environmental Pollution 217 (2016): 124-33. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2016.01.039.

[7] Hagmar, Lars et al. “Intra-individual variations and time trends 1991-2001 in human serum levels of PCB, DDE and hexachlorobenzene.” Chemosphere 64, 9 (2006): 1507-13. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2005.12.054.

[8] Helmfrid, Ingela et al. “Health effects and exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and metals in a contaminated community.” Environment International 44 (2012): 53-8. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2012.01.009.

[9] Choi, Anna L et al. “Does living near a Superfund site contribute to higher polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) exposure?.” Environmental Health Perspectives 114, 7 (2006): 1092-8. doi:10.1289/ehp.8827.

[10] Choi, Anna L et al. “Does living near a Superfund site contribute to higher polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) exposure?.” Environmental Health Perspectives 114, 7 (2006): 1092-8. doi:10.1289/ehp.8827.

[11] Zhang, Jingwen et al. “Environmental Polychlorinated Biphenyl Exposure and Breast Cancer Risk: A Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies.” PloS One 10, 11 (2015): e0142513. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0142513.

[12] Bachelet, Delphine et al. “Breast Cancer and Exposure to Organochlorines in the CECILE Study: Associations with Plasma Levels Measured at the Time of Diagnosis and Estimated during Adolescence.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, 2 (2019): 271. doi:10.3390/ijerph16020271.

[13] He, Yuanfang et al. “Adipose tissue levels of polybrominated diphenyl ethers and breast cancer risk in Chinese women: A case-control study.” Environmental Research 167 (2018): 160-168. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2018.07.009.

[14] Braathen, Marte et al. “Estrogenic effects of selected hydroxy polychlorinated biphenyl congeners in primary culture of Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar) hepatocytes.” Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 56, 1 (2009): 111-22. doi:10.1007/s00244-008-9163-0.

[15] Silver, Sharon R et al. “Occupational exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls and risk of breast cancer.” Environmental Health Perspectives 117, 2 (2009): 276-82. doi:10.1289/ehp.11774.

[16] Salehi, Fariba et al. “Review of the etiology of breast cancer with special attention to organochlorines as potential endocrine disruptors.” Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health 11, 3-4 (2008): 276-300. doi:10.1080/10937400701875923.

[17] Golden, Robert, and Renate Kimbrough. “Weight of evidence evaluation of potential human cancer risks from exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls: an update based on studies published since 2003.” Critical Reviews in Toxicology 39, 4 (2009): 299-331. doi:10.1080/10408440802291521.

[18] Muscat, Joshua E et al. “Adipose concentrations of organochlorine compounds and breast cancer recurrence in Long Island, New York.” Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 12, 12 (2003): 1474-8.

[19] Agency for Toxic Substances & Disease Registry. “Toxic Substances Portal – Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs).” Last modified July 2014. http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxfaqs/TF.asp?id=140&tid=26.

[20] Laden, Francine et al. “Polychlorinated biphenyls, cytochrome P450 1A1, and breast cancer risk in the Nurses’ Health Study.” Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 11, 12 (2002): 1560-5.