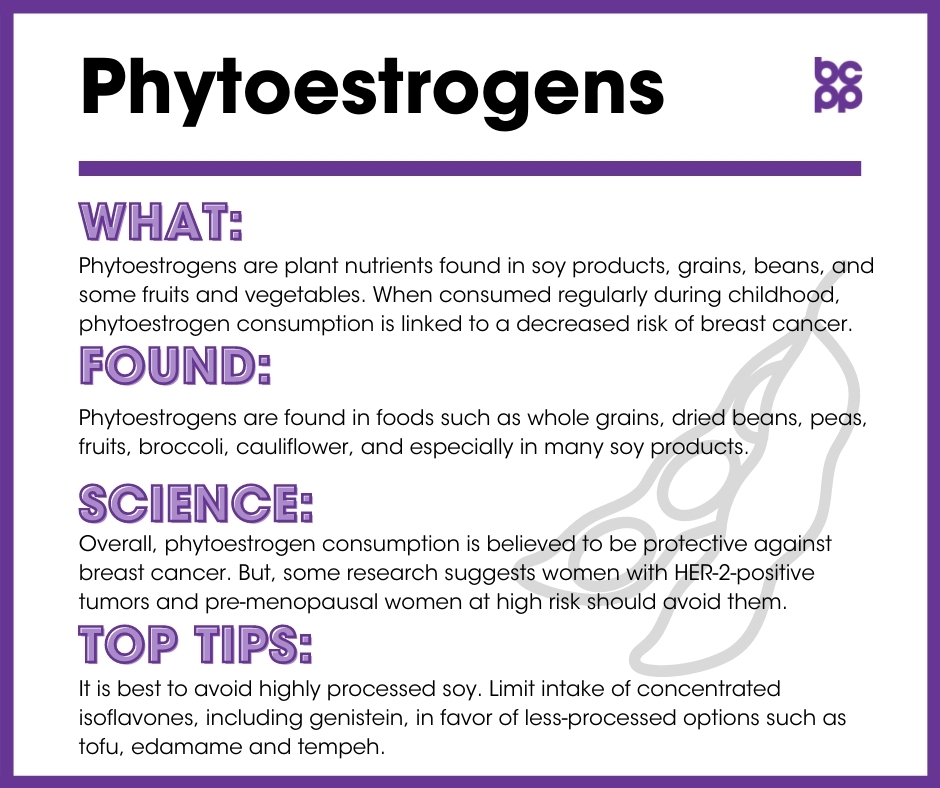

Phytoestrogens

What are phytoestrogens?

Phytoestrogens are plant compounds that are estrogen-like in their cellular actions. [1]

Where are phytoestrogens found?

Phytoestrogens are found in foods such as whole grains, dried beans, peas, fruits, broccoli, cauliflower and especially in many soy products.[2],[3] Common phytoestrogens found in fruits, whole grains and seeds are called lignans.[4] Those found in soy products are isoflavones. [5]

Are phytoestrogens protective or a risk for breast cancer?

Some studies link consumption of lignans (phytoestrogens in fruits, grains and seeds) to reduced tumor cell growth:

- When lignan was added to the highly aggressive and invasive human breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-321, researchers observed signs associated with a decrease in cell proliferation.[6]

- In women with recent diagnoses of breast cancer, higher intake of flax increased cell death, therefore leading to slower growth of the tumor and lower proliferative rates.[7]

Some studies link consumption of soy products to reduced breast cancer risk and reduced risk of recurrence:

- Phytoestrogens, especially when consumed regularly during childhood, have been linked to a decreased risk of breast cancer.[8] One study found that a decreased risk of breast cancer was associated with greater soy intake during childhood, adolescence and adulthood, and the protective effect of dietary soy intake during childhood was the strongest.[9]

- For Chinese women previously diagnosed with breast cancer, higher consumption of soy was correlated with decreased recurrence of cancer.[10]

- In one strain of rats, dietary exposure to soy from conception through adulthood decreased the incidence of mammary tumors in adult animals by 20 percent.[11]

- Exposure of another strain of rats to phytoestrogens in soy from conception through weaning led to decreases in tumor number and incidence.[12]

Several studies have found evidence that complicates the relationship between phytoestrogens and the incidence of breast cancer. This evidence indicates that the effect of phytoestrogens, especially those found in soy products, is not always protective; in several cases, these phytoestrogens have actually shown a proliferative effect, depending on several factors. Age, phytoestrogen type, cancer subtype, concentration and dose have all been observed as factors that determine how the phytoestrogens will affect breast cancer. Here are examples of studies that have found contrasting evidence:

- In one study of Korean women, dietary soy intake was associated with a decreased rate of recurrence when cancer was HER-2 negative, but an increased rate of recurrence in women whose tumors were HER-2 positive.[13]

- In predominantly pre-menopausal women who were considered to be at high risk for breast cancer, isoflavone intake through diet actually increased growth of breast cells in the lab.[14]

- In one study examining the effects of different types and concentrations of phytoestrogens, low doses of genistein (also found in soy) increased the growth of breast cells in the lab, whereas higher concentrations increased cell death.[15]

- In cultured MCF-7 cells, the soy phytoestrogen daidzein slightly enhanced cell proliferation, but resveratrol, a phytoestrogen found in grapes and red wine, decreased tumor cell proliferation.[16]

- Isoflavones that occur naturally in soy flour have different effects than isoflavones that have been purified from soy flour. Naturally occurring isoflavones may have an inhibitory effect on the proliferative effects that isolated isoflavones have.

What about effects of exposures to phytoestrogens in women who have been diagnosed with breast cancer?

- In a study of women who had undergone surgery for breast cancer and then received either tamoxifen or anastrozole (an aromatase inhibitor), 5 years following treatment there was no association between soy isoflavone levels at diagnosis and either subsequent breast cancer recurrence or mortality in premenopausal women.In postmenopausal women, the associations between isoflavone levels at the time of diagnosis and breast cancer recurrence were influenced by both the receptor subtype of their tumors, as well as the chemical treatment the women underwent. Overall, In women with ER+/PR+ tumors, higher isoflavone levels were associated with lower levels of later recurrence, while other receptor profiles were not associated with positive or negative associations. In postmenopausal women with ER+/PR+ tumors who took anastrozole, higher isoflavone levels at diagnosis were associated with decreased risk of breast cancer recurrence. The effect was the opposite for women taking tamoxifen.[17]

- In general, isoflavone intake appears to have a greater protective impact on later breast cancer recurrence and mortality among postmenopausal breast cancer patients, compared to premenopausal breast cancer patients.

- Furthermore, post-menopausal Asian women may be less likely to experience recurrence or mortality than women from other groups. Long term dietary differences across the cultures, including differences in the way of producing soy products, may be associated with different metabolic responses to ingesting soy.[18]

- Results of many studies addressing the relationship between soy isoflavone intake and decreased mortality from breast cancer are more consistent and robust than are the studies exploring the linkage to later recurrence.[19],[20]

- Isoflavone intake also has some negative outcomes on bone density. In women followed for 5 years following their diagnosis of breast cancer, soy intake across the post-diagnostic period was inversely associated with bone mineral density and positively associated with an increased risk for osteoporosis.[21]

- In terms of phytoestrogen lignans, found in soy but also many whole grains and beans, several studies have reported a protective effect of higher dietary levels at time of diagnosis against subsequent all-cause mortality as well as mortality linked to breast cancer in postmenopausal women.[22]

- At least one study has indicated that while higher lignan intake may be protective against increases in mortality over the 6 years following diagnosis for postmenopausal women, it is associated with increased mortality in premenopausal women at the end of 6 years.[23]

Who is most likely to receive benefits from phytoestrogens?

The link between phytoestrogens and a decreased risk of developing breast cancer is most commonly seen in people who have been consuming phytoestrogens through their daily diet since childhood.[24],[25] Asian diets generally incorporate more soy products than Western diets do throughout childhood and adulthood, allowing for more exposure to a balanced diet including phytoestrogens and the potential benefits they produce with respect to breast cancer.[26],[27]

How can I avoid highly processed phytoestrogens?

Since highly processed and concentrated phytoestrogens may have different effects on breast tumor cells, it is best to avoid highly processed soy. Limit intake of concentrated isoflavones, including genistein, in favor of less-processed options such as tofu, edamame and tempeh.

Updated 2019

[2] Sakamoto, Takako et al. “Effects of diverse dietary phytoestrogens on cell growth, cell cycle and apoptosis in estrogen-receptor-positive breast cancer cells.” The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry 21, 9 (2010): 856-64. doi:10.1016/j.jnutbio.2009.06.010.

[3] Andres, Susanne et al. “Risks and benefits of dietary isoflavones for cancer.” Critical Reviews in Toxicology 41, 6 (2011): 463-506. doi:10.3109/10408444.2010.541900.

[4] Seibold, Petra et al. “Enterolactone concentrations and prognosis after postmenopausal breast cancer: assessment of effect modification and meta-analysis.” International Journal of Cancer 135, 4 (2014): 923-33. doi:10.1002/ijc.28729.

[5] Rice, Suman, and Saffron A Whitehead. “Phytoestrogens and breast cancer–promoters or protectors?.” Endocrine-Related Cancer 13, 4 (2006): 995-1015. doi:10.1677/erc.1.01159.

[6] Xiong, Xiang-Yang et al. “Inhibitory Effects of Enterolactone on Growth and Metastasis in Human Breast Cancer.” Nutrition and Cancer 67, 8 (2015): 1324-32. doi:10.1080/01635581.2015.1082113.

[7] Flower, Gillian et al. “Flax and Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review.” Integrative Cancer Therapies 13, 3 (2014): 181-92. doi:10.1177/1534735413502076.

[8] Lee, Sang-Ah et al. “Adolescent and adult soy food intake and breast cancer risk: results from the Shanghai Women’s Health Study.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 89, 6 (2009): 1920-6. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2008.27361.

[9] Korde, Larissa A et al. “Childhood soy intake and breast cancer risk in Asian American women.” Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 18,4 (2009): 1050-9. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0405.

[10] Shu, Xiao Ou et al. “Soy food intake and breast cancer survival.” JAMA 302, 22 (2009): 2437-43. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.1783.

[11] Möller FJ et al. “Soy isoflavone exposure through all life stages accelerates 17β-estradiol-induced mammary tumor onset and growth, yet reduces tumor burden, in ACI rats.” Archives of Toxicology 90, 8 (2016): 1907-1916. doi:10.1007/s00204-016-1674-2.

[12] Phrakonkham, P et al. “Dietary exposure in utero and during lactation to a mixture of genistein and an anti-androgen fungicide in a rat mammary carcinogenesis model.” Reproductive Toxicology 54 (2015): 101-9. doi:10.1016/j.reprotox.2014.05.016.

[13] Wu, Ying-Chao et al. “Meta-analysis of studies on breast cancer risk and diet in Chinese women.” International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Medicine 8, 1 (2015): 73-85.

[14] Khan, Seema A et al. “Soy isoflavone supplementation for breast cancer risk reduction: a randomized phase II trial.” Cancer Prevention Research 5, 2 (2012): 309-19. doi:10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0251.

[15] Sakamoto, Takako et al. “Effects of diverse dietary phytoestrogens on cell growth, cell cycle and apoptosis in estrogen-receptor-positive breast cancer cells.” The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry 21, 9 (2010): 856-64. doi:10.1016/j.jnutbio.2009.06.010.

[16] Sakamoto, Takako et al. “Effects of diverse dietary phytoestrogens on cell growth, cell cycle and apoptosis in estrogen-receptor-positive breast cancer cells.” The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry 21, 9 (2010): 856-64. doi:10.1016/j.jnutbio.2009.06.010.

[17] Kang, Xinmei et al. “Effect of soy isoflavones on breast cancer recurrence and death for patients receiving adjuvant endocrine therapy.” CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal 182, 17 (2010): 1857-62. doi:10.1503/cmaj.091298.

[18] He, Fen-Jin and Jin-Qiang Chen. “Consumption of soybean, soy foods, soy isoflavones and breast cancer incidence: Differences between Chinese women and women in Western countries and possible mechanisms.” Food Science and Human Wellness 2 (2013): 146–61. doi:10.1016/j.fshw.2013.08.002.

[19] Fritz, Heidi et al. “Soy, red clover, and isoflavones and breast cancer: a systematic review.” PloS One 8, 11 (2013): e81968. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0081968.

[20] He, Fen-Jin and Jin-Qiang Chen. “Consumption of soybean, soy foods, soy isoflavones and breast cancer incidence: Differences between Chinese women and women in Western countries and possible mechanisms.” Food Science and Human Wellness 2 (2013): 146–61. doi:10.1016/j.fshw.2013.08.002.

[21] Baglia, Michelle L et al. “Soy isoflavone intake and bone mineral density in breast cancer survivors.” Cancer Causes & Control 26, 4 (2015): 571-80. doi:10.1007/s10552-015-0534-3.

[22] Seibold, Petra et al. “Enterolactone concentrations and prognosis after postmenopausal breast cancer: assessment of effect modification and meta-analysis.” International Journal of Cancer 135, 4 (2014): 923-33. doi:10.1002/ijc.28729.

[23] Kyrø, Cecilie et al. “Pre-diagnostic polyphenol intake and breast cancer survival: the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) cohort.” Breast Cancer Research and Treatment 154, 2 (2015): 389-401. doi:10.1007/s10549-015-3595-9.

[24] Korde, Larissa A et al. “Childhood soy intake and breast cancer risk in Asian American women.” Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 18,4 (2009): 1050-9. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0405.

[25] Zhang, Min et al. “Dietary intake of isoflavones and breast cancer risk by estrogen and progesterone receptor status.” Breast Cancer Research and Treatment 118, 3 (2009): 553-63. doi:10.1007/s10549-009-0354-9.

[26] Andres, Susanne et al. “Risks and benefits of dietary isoflavones for cancer.” Critical Reviews in Toxicology 41, 6 (2011): 463-506. doi:10.3109/10408444.2010.541900.

[27] Rice, Suman, and Saffron A Whitehead. “Phytoestrogens and breast cancer–promoters or protectors?.” Endocrine-Related Cancer 13, 4 (2006): 995-1015. doi:10.1677/erc.1.01159.