With BCPP Science Team Dr. Rainbow Rubin, PhD, MPH, and Pujeeta Chowdhary, MPH

In this issue of ‘Ask A Scientist,’ we explore the roots of Black History Month and how it intersects with environmental justice and racially-bound health disparities. We’ll also provide readers with educational resources on fighting racial inequality and reducing breast cancer risk for all.

Why February?

Black History Month can be traced back to 1926, when African American historian and activist Dr. Carter G. Woodson, known as the “father of Black history,” established ‘Negro History Week’ during the second week of February. Dr. Woodson noticed that society didn’t recognize Black individuals’ accomplishments in science, technology, education, or other subjects and sought to advocate for social equality and celebrate Black thinkers’ achievements. He chose the second week in February because it was around this time of year that Black Americans would come together to celebrate emancipation and the birthdays of two impactful historical leaders who strongly shaped the freedom and equality of Black Americans: Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglas. The awareness and interest in Black history in America grew, and in 1976, President Ford officially recognized February as Black History Month.[1]

Black Americans and Environmental Injustice

Although we’ve made some progress toward racial equity, racially defined environmental injustice has plagued our country since the start of the sustainability movement in the 1970s.

In the U.S., the racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic makeup of our neighborhoods, towns, and cities are the top indicators determining where highways, toxic facilities, and waste sites are built. Today, these frontline communities are disproportionately exposed to harmful chemicals through air and water pollution, both of which are known to increase residents’ risk of breast cancer and other chronic diseases.

One of the earliest examples of this phenomenon was in Warren County, North Carolina, a primarily Black rural community, in the late 1970s. Devastatingly, the state government chose this area as a dumping ground for soil contaminated with carcinogenic polychlorinated bisphenols (PCBs).[2] When residents complained of PCBs leaching into their drinking water, their concerns were wrongfully dismissed. Residents protested nonviolently, lying down on roads leading to landfills and physically blocking the path of trucks carrying dangerous chemicals. Unfortunately, residents lost the battle. This is simply one of many accounts of the racially charged environmental injustice spanning and impacting countless U.S. communities.

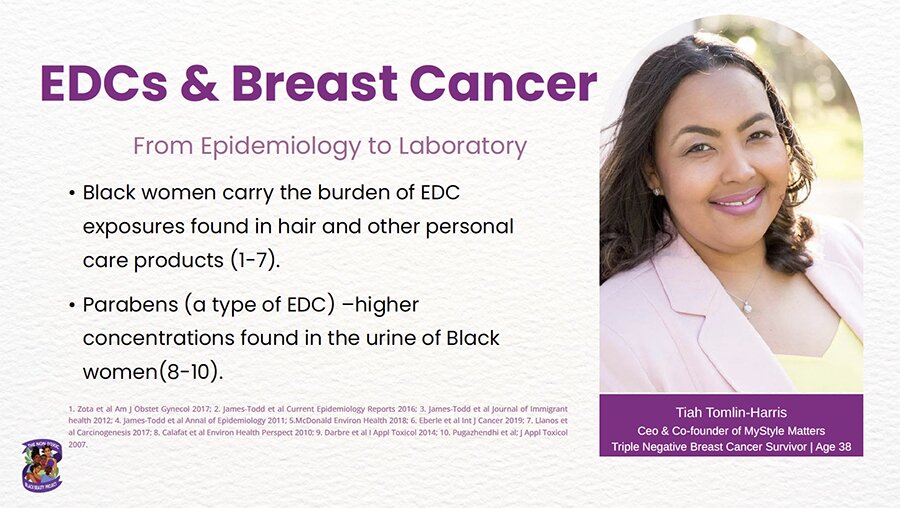

Today, Black scholars such as Dr. Tamarra M James-Todd, Dr. Adana A. M. Llanos, Dr. Jasmine McDonald, and Dr. Dede Teteh document the racial and ethnic disparities in health outcomes in scientific literature. However, much more work is needed to create meaningful change.

Breast Cancer in Black Women

Health disparities related to breast cancer are prevalent, specifically between Black and White women. Since 2012, breast cancer rates between Black and White women remain relatively similar; however, Black women have a 40% higher breast cancer mortality rate — the highest of any U.S. racial or ethnic group.[3]

Additionally,

- Breast cancer incidence is higher among Black women than White women under 40.[4]

- Black women are more likely to develop more aggressive forms of breast cancer (triple-negative breast cancer) than other racial or ethnic groups.[4]

- Breast cancer is the leading cause of cancer death in the U.S. for Black women.[5]

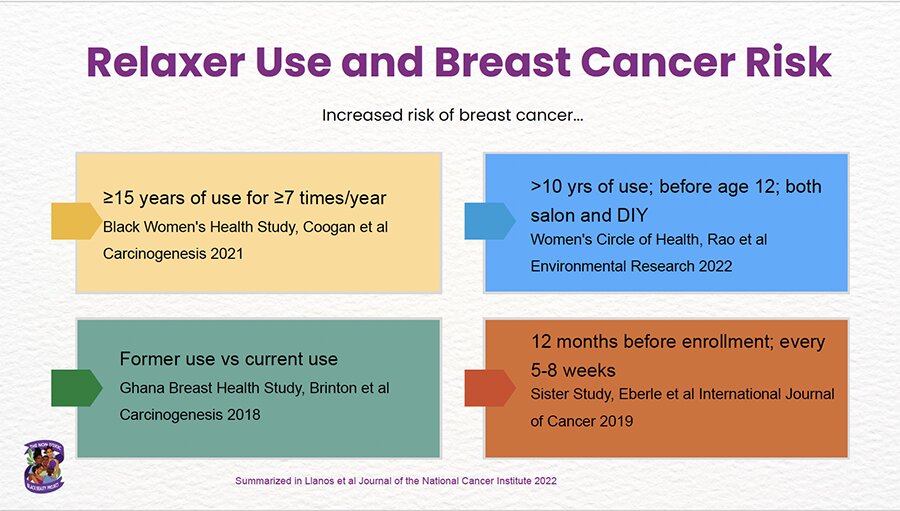

- Black women who use hair dye at least every 5–8 weeks have a 60% risk of higher breast cancer.[5]

Black and African American women are of diverse ethnicities, cultures, and regions, including African, Caribbean, Afro-Latina, and others. Unfortunately, women of color have distinct breast cancer risks uncaptured by current research or interventions. Increasing Black women’s representation in breast cancer research and clinical trials is essential to mitigate health inequity.

The Bench to Community Initiative (BCI) is an incredible project addressing this issue. BCI aims to research environmental determinants of breast cancer and reduce exposures in Black women specifically.

What is BCPP Doing?

BCPP advocates for laws and regulations addressing environmental justice concerns to prevent breast cancer and foster healthier communities. One of our most significant projects, called Charting Paths to Prevention, evaluates race, power, and inequities as major overarching factors influencing breast cancer risk.

We are working to develop community-level interventions to address the historical roots and ongoing trauma of systemic oppression based on race, ethnicity, income status, gender identity and orientation, sexual orientation, immigration status, disability, and other factors that may increase breast cancer risk. You can read more about this project here.

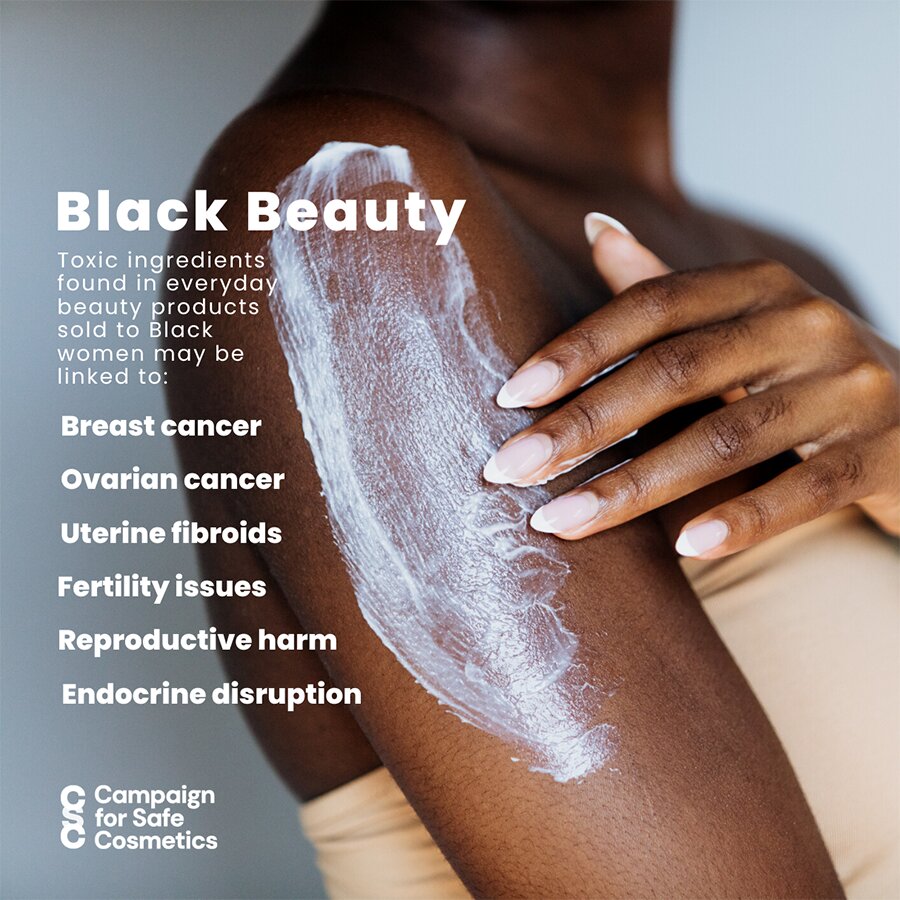

In 2020, we launched the Nontoxic Black Beauty Project to tackle environmental injustice in the beauty industry. Communities of color endure disproportionate chemical burdens from personal care products and face more adverse health outcomes.[6] Many of the chemicals found in these products are linked to breast cancer and other health conditions like uterine fibroids, infertility, and complications during pregnancy that negatively impact Black women and girls.[7] Using the latest scientific research, we created a “do not use” red list of toxic chemicals that Black-owned beauty brands can use to help formulate products free of harmful ingredients. Our database allows consumers to access products free of these ingredients and certified Nontoxic Black- owned beauty brands.

We also partner with individual communities to eliminate place-based exposure and achieve environmental justice. Our organizational partners in environmental justice include Coming Clean, Black Women for Wellness, Environmental Justice Health Alliance for Chemical Policy Reform, California Environmental Justice Alliance, Californians for a Green and Healthy Economy, and the individual members of these alliances and coalitions.

This training slide is part of the educational series for the Bench to Community Initiative.

This training slide is apart of the educational series for the Bench to Community Initiative.

Raise Awareness in YOUR House – What can YOU do?

- Educate yourself. Explore and learn about Black history and culture through resources, including books, television, and other media (see our recommended watching and reading lists below). Black Women for Wellness also publishes videos, newsletters, and podcasts and hosts meaningful events.

- Take action. Defend the health of communities of color and salon workers. These vulnerable populations are among the most highly exposed to toxic chemicals because of the products marketed to them or found in their workplaces. Tell your congress member to support #SaferBeautyforAll.

- Get involved with the Bench to Community Initiative (BCI) and help reduce adverse exposures in Black Women with breast cancer.

- Support Black-owned businesses and learn about our Nontoxic Black Beauty Project described above.

Celebrating the legacy and rich history of Black people this month is essential. However, we must continuously reflect on the victories and sacrifices that led us to where we are and continue the fight for racial equity and justice every day of the year.

Check out some recommendations below to learn more.

Recommended Watching:

Black Is King

Toni Morrison: Black Matters

I Am Not Your Negro

Hidden Figures

Marshall

Summer of Soul

Black History Month Virtual Festival: https://asalh.org/festival/

Recommended Readings:

Include books about Black History as part of reading materials for children, such as ABC Black History and Me by Queenbe Monyei, A Library by Nikki Giovanni, and Bright April by Marguerite de Angeli.

Medical Apartheid by Harriet A. Washington

The 1619 Project by Nikole Hannah-Jones

How to be an Antiracist by Ibram X. Kendi

Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot

Natural Nia by La Rhonda Crosby-Johnson

Also check out Black Women for Wellness’ list of Black authors and Oprah’s 30 Best Books by Black Authors list

This training slide is apart of the educational series for the Bench to Community Initiative.

Key Terms:

Environmental Justice: The concept that all people (regardless of origin, race, color, or income) have the right to equal environmental protection and natural resources, and can influence policies to protect their communities.

Black History Month: Occurs during the month of February when the achievements and sacrifices of Black Americans are remembered and honored.[8]

Frontline communities: These communities are often people of color and low-income populations living near industrial facilities. Daily exposure to toxic air pollution and lack of access to affordable and healthy food results in disproportionate health outcomes relative to the rest of the nation.

Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: Triple-negative breast cancer is a type of breast cancer that is especially difficult to treat, because it does not have the hormone receptors commonly found in breast cancer. These receptors are analogous to pathways that can be used to target the cancer; when there are less pathways, there are less treatment options.

Footnotes:

[1] https://asalh.org/about-us/about-black-history-month/. Accessed February 12, 2024.

[2] https://www.nrdc.org/stories/environmental-justice-movement. Accessed February 13, 2024

[3] Giaquinto, A.N., Sung, H., Miller, K.D., Kramer, J.L., Newman, L.A., Minihan, A., Jemal, A. and Siegel, R.L. (2022), Breast Cancer Statistics, 2022. CA A Cancer J Clin. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21754

[4] Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394-424.

[5] Carolyn E. Eberle,Dale P. Sandler,Kyla W. Taylor,Alexandra J. White. Hair dye and chemical straightener use and breast cancer risk in a large US population of black and white women, 2019. Int. J. Cancer: 147, 383-391 (2020).

[6] Jasmine A. McDonald, Adana A. M. Llanos, Taylor Morton, and Ami R. Zota, 2022: The Environmental Injustice of Beauty Products: Toward Clean and Equitable Beauty American Journal of Public Health 112, 50_53, https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2021.306606

[7] James-Todd TM, Chiu YH, Zota AR. Racial/ethnic disparities in environmental endocrine disrupting chemicals and women’s reproductive health outcomes: epidemiological examples across the life course. Curr Epidemiol Rep. 2016 Jun;3(2):161-180. doi: 10.1007/s40471-016-0073-9. Epub 2016 Mar 31. PMID: 28497013; PMCID: PMC5423735.

[8] https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/breast/triple-negative.htm, accessed February 14, 2024.