Tobacco Smoke

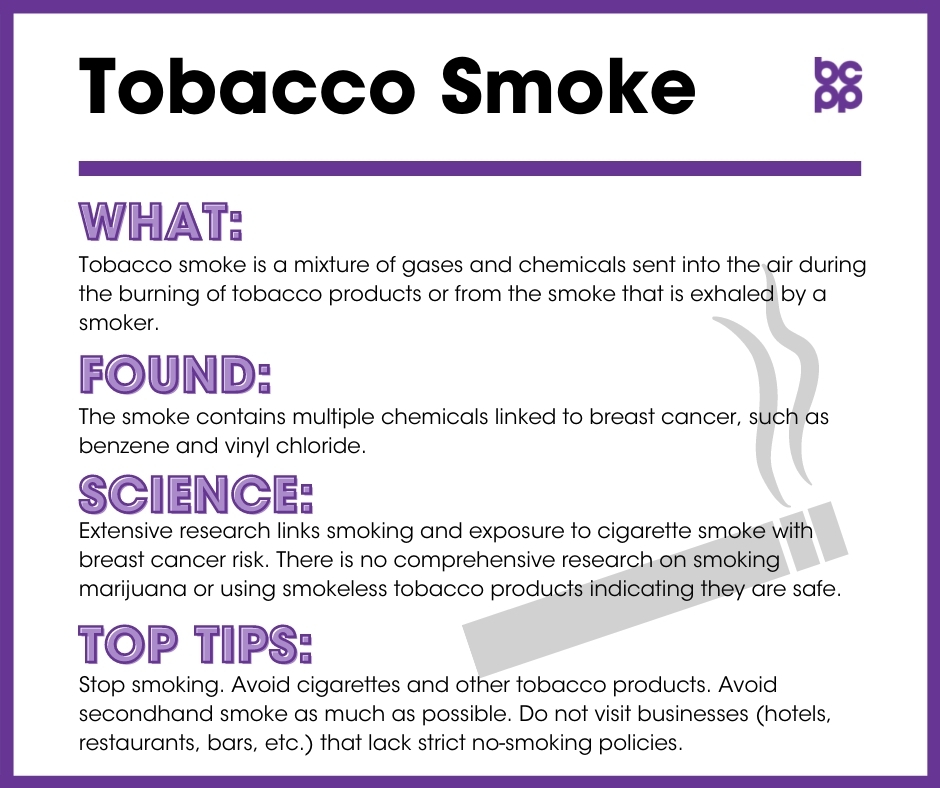

What is tobacco smoke?

Tobacco smoke is a mixture of gases and chemicals that is sent into the air during the burning of tobacco products or from the smoke that is exhaled by a smoker. The smoke that is present in the environment contains multiple chemicals linked to breast cancer, such as benzene and vinyl chloride, both designated as known carcinogens by the International Agency for Research on Cancer or the National Toxicology Program,[1],[2],[3] as well as 1, 3-butadiene, toluene, and nicotine-derived nitrosamine ketone (NNK) that may cause mammary tumors in animals.[4] NNK is a tobacco-specific carcinogen that studies have shown to increase tumor cell proliferation and the transformation of healthy breast epithelial cells into cancer cells.[5],[6],[7]

Passive smoke is the involuntary exposure to somebody else’s tobacco smoke. Passive smokers inhale secondhand smoke from the exhaled smoke of active smokers, and also from the smoke that emerges from smoldering tobacco. Of increasing concern are exposures to third hand smoke, that is, contamination from active smoking that remains in indoor environments long after first and second hand smoke has been released into the air. Third hand smoke is found in in many places, including carpets, furniture, blankets, toys, and even on walls. Over time, as the chemicals from second hand smoke break down, the concentrations of NNK rise and surpass levels found in both active and second-hand smoke residues.[8]

What evidence links active and passive smoking to breast cancer?

Cigarette smoking causes more than 480,000 deaths each year in the United States alone.[9] Tobacco smoke contains chemicals that have been linked to breast and other cancers.[10]

- The California Teachers Study, one of the largest studies to follow participants over time, found an increased risk of breast cancer among smokers. More specifically, the study revealed a heightened risk for those who began smoking during adolescence, those who had smoked for at least 5 years prior to their first full-term pregnancy, and those who were deemed long-term or heavy smokers.[11] This supported earlier studies that suggested that women who began smoking as adolescents had an increased risk of breast cancer.[12],[13],[14],[15],[16] A recent meta-analysis, however, did not find a relationship between initiation of smoking before a first-time pregnancy and breast cancer risk[17]. More research is needed to explore these inconsistent findings.

- Multiple studies support increased risk of breast cancer as a result of number of cigarettes smoked, duration of smoking, and age of smoking initiation. Results from the Canadian National Breast Screening Study revealed that smoking for a long period of time and smoking many cigarettes per day were both associated with increased rates of breast cancer.[18] The Nurses’ Health Study and the Women’s Health Initiative Study both indicated similar results, suggesting longer duration of smoking, greater quantities of cigarettes smoked, and younger age when starting to smoke were all positively linked to higher incidence rates of breast cancer.[19],[20]

- Researchers from the National Cancer Center in Japan reported an increased risk of breast cancer in pre-menopausal women for both active and passive smoking.[21] Research, however, has provided mixed data on the impact passive smoking has on breast cancer risk. The California Teachers Study, for example, revealed no apparent relationship with passive smoking and increased breast cancer risk,[22] while other studies found a positive association between regular exposure to passive smoke and breast cancer risk.[23],[24],[25] The Women’s Health Initiative found that passive smoke exposure lasting more than 10 years in childhood, 20 or more years for adults at home, and 10 years for adults at work was linked to increased risk of breast cancer.[26]

- While there is currently no direct research on exposures to third-hand smoke and breast cancer outcomes, the fact that NNK levels are highest in third-hand smoke leads scientists to hypothesize that these environmental exposures may well be associated with increased risk for developing NNK sensitive diseases, including perhaps breast cancer.[27]

What about effects of exposures to active and passive smoking in women who have been diagnosed with breast cancer?

- In a study of almost 5,000 women diagnosed with breast cancer, smoking at the time of diagnosis was associated with an increased risk of recurrence as compare with women who were never smokers. Several other studies support these findings. The results were strongest for women who were heavy smokers at the time of diagnosis.[28],[29]

- A series of comprehensive reviews have shown that women who are active smokers at the time of diagnosis with breast cancer are significantly more likely to die in the 5-10 years following diagnosis than are women who were never smokers. Much of this difference is covered by increased risk for dying from respiratory disorders and lung cancer, but there was also an increase in smokers dying from breast cancer during the post-diagnosis follow-up periods.[30],[31],[32]

- Continuing to smoke after diagnosis of breast cancer is associated with an increase in breast cancer specific mortality. Importantly, those women who stopped smoking after their diagnosis (compared to those that did not stop) were significantly less likely to die of either breast cancer or other cancers in the 6 years following their diagnoses.[33]

- Post-menopausal breast cancer patients with either luminal A or triple negative forms of breast cancer are particularly susceptible to the increases in mortality – both from breast cancer and from other diseases – as a consequence of smoking.[34]

- Continued active smoking at the time of breast reconstruction surgery following a diagnosis of breast cancer led to a more that 2-fold increase in surgical complications.[35]

Who is most likely to be exposed to tobacco smoke?

Those exposed include tobacco smokers, whether they use cigarettes, pipes, or vaping devices, and non-smokers around them who inhale air polluted with tobacco smoke. Current evidence suggests that both active and secondhand exposure can increase breast cancer risk, even though women who are exposed to secondhand smoke receive a much lower dose of carcinogens than do active smokers.[36],[37]

The Women’s Health Study indicated that 88 percent of people who have never smoked were exposed to passive smoking in their lifetime,[38] so most people will be exposed to tobacco smoke during their lifetime.

While everyone is vulnerable to exposures from third-hand smoke, children – especially toddlers—are especially vulnerable to both exposures to, and effects of, third hand smoke. For example, toddlers are more likely to roll around in contaminated carpets or to inhale dust particles containing NNK. During these critical times of development, these chemicals may have profound effects on developing systems[39], including breast tissue.

Who is most vulnerable to the health effects?

Overall, research suggests earlier exposures to tobacco smoke are of greater concern.

- Some studies indicate smoking before a first full-term pregnancy may increase the risk of a later diagnosis of breast cancer.[40],[41]

- Smoking during adolescence has been found to be associated with increased breast cancer risk.[42],[43],[44],[45],[46]

- Studies also suggest increased risk of breast cancer for pre-menopausal women.[47]

- Individuals who have smoked for a long time or have smoked heavily seemed to have higher risks for breast cancer.[[48]

What are the top tips to avoid exposure to tobacco smoke?

- Stop smoking. Avoid cigarettes and other tobacco products.

- Avoid secondhand smoke as much as possible.

- Avoid restaurants, hotels, etc. that do not maintain strict no-smoking policies.

What about smoking marijuana or using smokeless tobacco?

There is no comprehensive research on specific links between alternative uses of tobacco or smoking marijuana on risk of developing breast cancer although these behaviors expose people to many of the same toxic chemicals found in first-, second- and third hand smoke derived from use of tobacco cigarettes.

- Although marijuana use may be an important therapeutic intervention to address the symptoms of treatment for breast cancer,[49],[50]smoking marijuana exposes people to many of the same contaminants found in cigarette smoke, especially PAHs. Unlike cigarettes, most marijuana formulations do not contain nicotine.

- Use of snuff or chewing tobacco leads to a significant increase in NNK in the dust from homes of smokeless tobacco users, thereby exposing users and others in the vicinity to the toxic effects of this carcinogenic chemical that has been linked to increased breast cancer.[51]

- E-cig use, or vaping, results in the exposures to high levels of nicotine which, in turn, is metabolized to NNK. Although no studies have examined association of e-cig second hand vapors and breast cancer risk, one study has shown similar effects on brain activity of second hand tobacco smoke and second hand e-cig vapors.[52] Another concern with vaping is the use of undisclosed flavorings, which may have their own health effects, and also make the products attractive to teens and young adults[53].

Additional Resources

- Smoking Before the First Pregnancy and the Risk of Breast Cancer: A Meta-Analysis.

- Association of active and passive smoking with risk of breast cancer among postmenopausal women: a prospective cohort study.

- A Report of the Surgeon General: How Tobacco Smoke Causes Disease… what it means to you.

- The Health Consequences of Smoking – 50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General Executive Summary.

Updated 2019

[2] National Toxicology Program, Department of Health and Human Services. “Benzene.” Lass modified November 3, 2016. http://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/ntp/roc/content/profiles/benzene.pdf.

[3] National Toxicology Program, Department of Health and Human Services. “Benzene.” Lass modified November 3, 2016. http://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/ntp/roc/content/profiles/benzene.pdf.

[4] Chen, Zhi-Bo et al. “Effects of tobacco-specific carcinogen 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK) on the activation of ERK1/2 MAP kinases and the proliferation of human mammary epithelial cells.” Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology 22, 3 (2006): 283-91. doi:10.1016/j.etap.2006.04.001.

[5] Mei, Jianxun et al. “Transformation of non-cancerous human breast epithelial cell line MCF10A by the tobacco-specific carcinogen NNK.” Breast Cancer Research and Treatment 79, 1 (2003): 95-105. doi:10.1023/a:1023326121951.

[6] Chen, Zhi-bo et al. “Tobacco-specific carcinogen 4-(methylnitrosoamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK) activating ERK1/2 MAP kinases and stimulating proliferation of human mammary epithelial cells.” Chemical Research in Chinese Universities 23, 1 (2007): 76-80. doi:10.1016/S1005-9040(07)60015-4.

[7] Siriwardhana, Nalin et al. “Precancerous model of human breast epithelial cells induced by NNK for prevention.” Breast Cancer Research and Treatment 109, 3 (2008): 427-41. doi:10.1007/s10549-007-9666-9.

[8] Jacob, Peyton 3rd et al. “Thirdhand Smoke: New Evidence, Challenges, and Future Directions.” Chemical Research in Toxicology 30, 1 (2017): 270-294. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrestox.6b00343.

[9] National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on Smoking and Health. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US), 2014.

[10] State of California Air Resources Board. “Appendix III: Proposed Identification of Environmental Tobacco Smoke as a Toxic Air Contaminant.” Last modified June 24, 2005. http://oehha.ca.gov/media/downloads/air/report/app32005.pdf.

[11] Reynolds, Peggy et al. “Active smoking, household passive smoking, and breast cancer: evidence from the California Teachers Study.” Journal of the National Cancer Institute 96, 1 (2004): 29-37. doi:10.1093/jnci/djh002.

[12] Band, Pierre R et al. “Carcinogenic and endocrine disrupting effects of cigarette smoke and risk of breast cancer.” Lancet 360, 9339 (2002): 1044-9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11140-8.

[13] Calle, E E et al. “Cigarette smoking and risk of fatal breast cancer.” American Journal of Epidemiology 139, 10 (1994): 1001-7. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116939.

[14] Gram, Inger T. et al. “Breast Cancer Risk Among Women Who Start Smoking as Teenagers.” Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers and Prevention 14, 1 (2005): 61–66.

[15] Johnson, K C et al. “Passive and active smoking and breast cancer risk in Canada, 1994-97.” Cancer Causes & Control 11, 3 (2000): 211-21. doi:10.1023/a:1008906105790.

[16] Marcus, P M et al. “The associations of adolescent cigarette smoking, alcoholic beverage consumption, environmental tobacco smoke, and ionizing radiation with subsequent breast cancer risk (United States).” Cancer Causes & Control 11, 3 (2000): 271-8. doi:10.1023/a:1008911902994.

[17] DeRoo, Lisa A et al. “Smoking before the first pregnancy and the risk of breast cancer: a meta-analysis.” American Journal of Epidemiology 174, 4 (2011): 390-402. doi:10.1093/aje/kwr090.

[18] Cui, Yan et al. “Cigarette smoking and breast cancer risk: update of a prospective cohort study.” Breast Cancer Research and Treatment 100, 3 (2006): 293-9. doi:10.1007/s10549-006-9255-3.

[19] Xue, Fei et al. “Cigarette smoking and the incidence of breast cancer.” Archives of Internal Medicine 171, 2 (2011): 125-33. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2010.503.

[20] Luo, Juhua et al. “Association of active and passive smoking with risk of breast cancer among postmenopausal women: a prospective cohort study.” BMJ 342 (2011): d1016. doi:10.1136/bmj.d1016.

[21] Hanaoka, Tomoyuki et al. “Active and passive smoking and breast cancer risk in middle-aged Japanese women.” International Journal of Cancer 114, 2 (2005): 317-22. doi:10.1002/ijc.20709.

[22] Reynolds, Peggy et al. “Active smoking, household passive smoking, and breast cancer: evidence from the California Teachers Study.” Journal of the National Cancer Institute 96, 1 (2004): 29-37. doi:10.1093/jnci/djh002.

[23] Johnson, K C et al. “Passive and active smoking and breast cancer risk in Canada, 1994-97.” Cancer Causes & Control 11, 3 (2000): 211-21. doi:10.1023/a:1008906105790.

[24] Johnson, Kenneth C et al. “Active smoking and secondhand smoke increase breast cancer risk: the report of the Canadian Expert Panel on Tobacco Smoke and Breast Cancer Risk (2009).” Tobacco Control 20, 1 (2011): e2. doi:10.1136/tc.2010.035931.

[25] Morabia, A et al. “Relation of breast cancer with passive and active exposure to tobacco smoke.” American Journal of Epidemiology 143, 9 (1996): 918-28. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008835.

[26] Luo, Juhua et al. “Association of active and passive smoking with risk of breast cancer among postmenopausal women: a prospective cohort study.” BMJ 342 (2011): d1016. doi:10.1136/bmj.d1016.

[27] Jacob, Peyton 3rd et al. “Thirdhand Smoke: New Evidence, Challenges, and Future Directions.” Chemical Research in Toxicology 30, 1 (2017): 270-294. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrestox.6b00343.

[28] Lafourcade, Alexandre et al. “Factors associated with breast cancer recurrences or mortality and dynamic prediction of death using history of cancer recurrences: the French E3N cohort.” BMC Cancer 18, 1 (2018): 171. doi:10.1186/s12885-018-4076-4.

[29] Nechuta, Sarah et al. “A pooled analysis of post-diagnosis lifestyle factors in association with late estrogen-receptor-positive breast cancer prognosis.” International Journal of Cancer 138, 9 (2016): 2088-97. doi:10.1002/ijc.29940.

[30] Bérubé, Sylvie et al. “Smoking at time of diagnosis and breast cancer-specific survival: new findings and systematic review with meta-analysis.” Breast Cancer Research 16, 2 (2014): R42. doi:10.1186/bcr3646.

[31] Braithwaite, Dejana et al. “Smoking and survival after breast cancer diagnosis: a prospective observational study and systematic review.” Breast Cancer Research and Treatment 136, 2 (2012): 521-33. doi:10.1007/s10549-012-2276-1.

[32] Nechuta, Sarah et al. “A pooled analysis of post-diagnosis lifestyle factors in association with late estrogen-receptor-positive breast cancer prognosis.” International Journal of Cancer 138, 9 (2016): 2088-97. doi:10.1002/ijc.29940.

[33] Passarelli, Michael N et al. “Cigarette Smoking Before and After Breast Cancer Diagnosis: Mortality From Breast Cancer and Smoking-Related Diseases.” Journal of Clinical Oncology 34, 12 (2016): 1315-22. doi:10.1200/JCO.2015.63.9328.

[34] Seibold, Petra et al. “Pre-diagnostic smoking behaviour and poorer prognosis in a German breast cancer patient cohort – Differential effects by tumour subtype, NAT2 status, BMI and alcohol intake.” Cancer Epidemiology 38, 4 (2014): 419-26. doi:10.1016/j.canep.2014.05.006.

[35] Wengler, Craig A et al. “Determinants of short and long term outcomes in patients undergoing immediate breast reconstruction following neoadjuvant chemotherapy.” Journal of Surgical Oncology 116, 7 (2017): 797-802. doi:10.1002/jso.24741.

[36] Ambrosone, Christine B. et al. “Cigarette smoking, N-acetyltransferase 2 polymorphisms, and breast cancer risk.” JAMA 276, 18 (1996): 1494–1501. doi:10.1001/jama.1996.03540180050032.

[37] Morabia, A et al. “Relation of breast cancer with passive and active exposure to tobacco smoke.” American Journal of Epidemiology 143, 9 (1996): 918-28. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008835.

[38] Luo, Juhua et al. “Association of active and passive smoking with risk of breast cancer among postmenopausal women: a prospective cohort study.” BMJ 342 (2011): d1016. doi:10.1136/bmj.d1016.

[39] Jacob, Peyton 3rd et al. “Thirdhand Smoke: New Evidence, Challenges, and Future Directions.” Chemical Research in Toxicology 30, 1 (2017): 270-294. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrestox.6b00343.

[40] Cui, Yan et al. “Cigarette smoking and breast cancer risk: update of a prospective cohort study.” Breast Cancer Research and Treatment 100, 3 (2006): 293-9. doi:10.1007/s10549-006-9255-3.

[41] Xue, Fei et al. “Cigarette smoking and the incidence of breast cancer.” Archives of Internal Medicine 171,2 (2011): 125-33. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2010.503.

[42] Band, Pierre R et al. “Carcinogenic and endocrine disrupting effects of cigarette smoke and risk of breast cancer.” Lancet 360, 9339 (2002): 1044-9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11140-8.

[43] Calle, E E et al. “Cigarette smoking and risk of fatal breast cancer.” American Journal of Epidemiology 139, 10 (1994): 1001-7. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116939.

[44] Gram, Inger T. et al. “Breast Cancer Risk Among Women Who Start Smoking as Teenagers.” Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers and Prevention 14, 1 (2005): 61–66.

[45] Johnson, Kenneth C et al. “Active smoking and secondhand smoke increase breast cancer risk: the report of the Canadian Expert Panel on Tobacco Smoke and Breast Cancer Risk (2009).” Tobacco Control 20, 1 (2011): e2. doi:10.1136/tc.2010.035931.

[46] Marcus, P M et al. “The associations of adolescent cigarette smoking, alcoholic beverage consumption, environmental tobacco smoke, and ionizing radiation with subsequent breast cancer risk (United States).” Cancer Causes & Control 11, 3 (2000): 271-8. doi:10.1023/a:1008911902994.

[47] Hanaoka, Tomoyuki et al. “Active and passive smoking and breast cancer risk in middle-aged Japanese women.” International Journal of Cancer 114, 2 (2005): 317-22. doi:10.1002/ijc.20709.

[48] Reynolds, Peggy et al. “Active smoking, household passive smoking, and breast cancer: evidence from the California Teachers Study.” Journal of the National Cancer Institute 96, 1 (2004): 29-37. doi:10.1093/jnci/djh002.

[49] Bar-Lev Schleider, Lihi et al. “Prospective analysis of safety and efficacy of medical cannabis in large unselected population of patients with cancer.” European Journal of Internal Medicine 49 (2018): 37-43. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2018.01.023.

[50] Caffarel, María M et al. “Cannabinoids: a new hope for breast cancer therapy?.” Cancer Treatment Reviews 38, 7 (2012): 911-8. doi:10.1016/j.ctrv.2012.06.005.

[51] Whitehead, Todd P et al. “Tobacco alkaloids and tobacco-specific nitrosamines in dust from homes of smokeless tobacco users, active smokers, and nontobacco users.” Chemical Research in Toxicology 28, 5 (2015): 1007-14. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrestox.5b00040.

[52] Ponzoni, L et al. “Different physiological and behavioural effects of e-cigarette vapour and cigarette smoke in mice.” European Neuropsychopharmacology 25, 10 (2015): 1775-86. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2015.06.010.

[53] Drazen, Jeffrey M et al. “The Dangerous Flavors of E-Cigarettes.” The New England Journal of Medicine 380, 7 (2019): 679-680. doi:10.1056/NEJMe1900484.