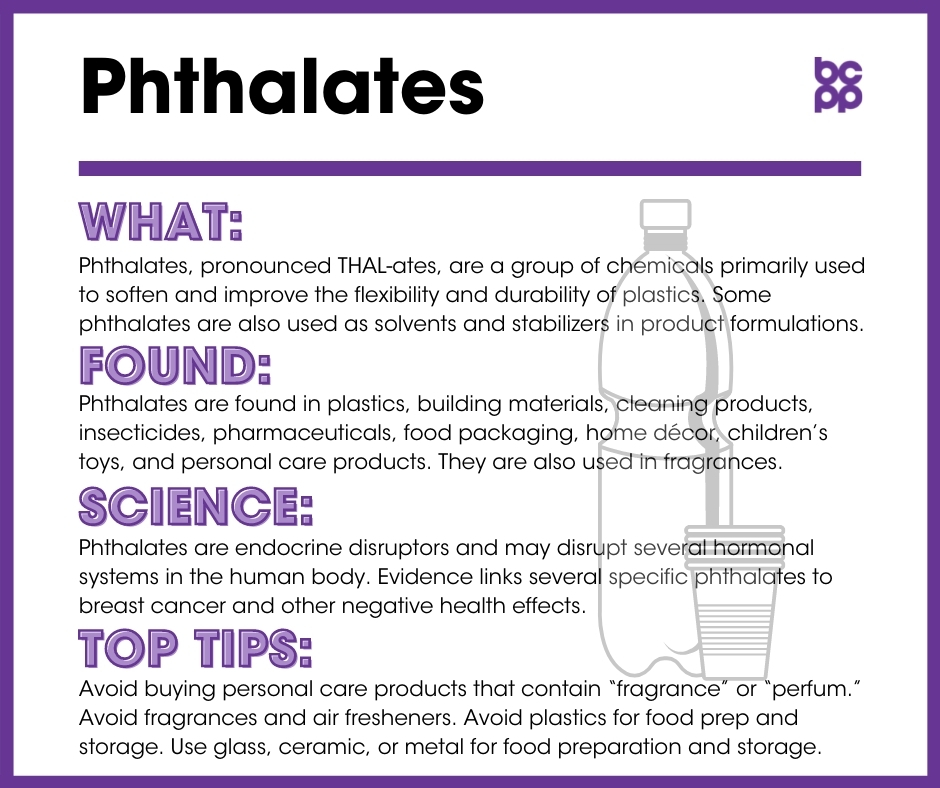

Phthalates

At a Glance

Phthalates are a group of chemicals used to soften and improve the flexibility and durability of plastics.

Phthalates are endocrine disruptors, and exposure to phthalates has been linked to breast cancer, developmental issues, decreased fertility, obesity and asthma.

Although some regulations ban phthalates in certain products intended specifically for young children, they are still widely used in many consumer products.

What are phthalates?

Phthalates, pronounced THAL-ates, are a group of chemicals primarily used to soften and improve the flexibility and durability of plastics. Some phthalates are also used as solvents and stabilizers in product formulations including personal care products and cosmetics.

Where are phthalates found?

Phthalates are found in a wide variety of products, including plastics, building materials, cleaning products, insecticides, pharmaceuticals, food packaging, home décor, children’s toys, and personal care products. There are two major groups of phthalates.

The first contains chemicals that are found in a variety of plastics and PVC-based products including:

- Shower curtains

- Vinyl floors

- PVC mini-blinds

- Furniture

- Soft-sided lunch boxes

- Plastic food wrap and packaging[1]

- Soft plastic food containers

- Medical devices such as intravenous (IV) bags and tubing

Examples of phthalates in this group include:

- Di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) and its main metabolites (breakdown products) mono-ethylhexyl phthalate (MEHP), mono-ethyl-5-hydroxyhexyl) phthalate (MEHHP)

- Di-n-octyl phthalate (DnOP) and its major metabolite mono-(3-carboxypropyl) phthalate (MCPP)

- Diisononyl phthalate (DiNP)

The second group of phthalates are found in solvents and a number of common products including:

- Cosmetics and personal care products

- Tampons and other feminine hygiene products[2]

- Fragrances in perfumes, personal care products, and many household products

- Hair spray

- Nail polish

- Air fresheners (plug-ins, sprays, and reed diffusers)

- Adhesives

- Paints

Examples of this second group of phthalates compounds include:

- Diethyl phthalate (DEP) and its major metabolite mono-ethyl phthalate (MEP)

- Dimethyl phthalate (DMP) and its major metabolite mono-methyl phthalate (MMP)

- Dibutyl phthalate (DBP) and its major metabolite mono-n-butyl phthalate (MBP)

- Diisobutyl phthalate (DiBP) and its major metabolite mono isobutyl phthalate (MiBP)

- Benzylbutyl phthalate (BzBP) and its major metabolite mono-benzyl butyl phthalate (MBzP)

Because phthalates are semi-volatile, they can be found in indoor air and dust.[3] People are exposed to phthalates by inhalation, ingestion, intravenous absorption (resulting from medical injection procedures[4]) and skin absorption.[5]

What evidence links phthalates to breast cancer?

Phthalates are endocrine disruptors and may disrupt several hormonal systems in the human body, including the estrogen, progesterone and androgen systems. Evidence links several specific phthalates to breast cancer and other negative health effects.

- In a study from Mexico, exposures to higher levels of diethyl phthalate (DEP) and its metabolite (breakdown product) mono-ethyl phthalate (MEP) were associated with increased risk for developing breast cancer, especially in premenopausal women. Higher urinary levels of metabolites of monobutyl phthalate (MBP) and di-n-octyl phthalate (DnOP) were associated with lower levels of breast cancer.[6]

- The Multiethnic Cohort Study examined the possible relationship between urinary phthalate and phthalate metabolite levels in women from 5 major racial/ethnic categories. Urine sample were taken on average 5.5 years before diagnosis of breast cancer, or from women of the same age and racial/ethnic identities who had not developed the disease. Women with the highest levels of DEHP metabolites had an increased risk for developing breast cancer, especially hormone-receptor positive cancer. This effect was particularly pronounced in Native Hawaiian women.[7]

- Benzyl butyl phthalate (BzBP) and dibutyl phthalate (DBP) have been shown to be weakly estrogenic, cause estrogen-triggered cell responses, and act in conjunction with the body’s own estrogens.[8]

- BzBP, DBP, and diisobutyl phthalate (DiBP) have been shown to bind to androgen receptors.[9]

- BzBP and DBP have been shown to cause cell proliferation, tumor formation, and malignant invasion of breast cancer cells that are low in or lack hormone receptors, indicating that there are negative health effects of phthalates beyond their direct impact on the estrogen-regulated systems.[10]

- High levels of diethyl phthalate (DEP) have been linked to infertility in men, while high levels of DEP and DBP have been linked to infertility in women.[11]

- Exposure to dimethyl phthalate (DMP) has been associated with early breast development, or thelarche, in girls.[12] Early breast development has been linked to an increased risk of developing breast cancer later in life.[13]

- BzBP, DBP and bis(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) have been shown in laboratory studies to increase growth of human breast cancer cells[14] and decrease the efficacy of tamoxifen, a drug commonly used to treat breast cancer.[15]

- DEHP interferes with the progesterone receptor system leading to increased proliferation of human breast cancer cells.[16]

- DBP, BzBP, and DEHP have been shown to affect the androgen system (“male” hormones) and may cause physical abnormalities in male offspring of exposed mothers, such as undescended testes, reduced distance between the anus and genitals, and other effects that would indicate a problem with normal fetal development and sex differentiation.[17],[18],[19]

- Phthalate exposure is also associated with diabetes,[20] the onset and exacerbation of asthma,[21],[22] and possibly obesity.[23]

What about effects of exposures to phthalates in women who have been diagnosed with breast cancer?

- In a study following women diagnosed with breast cancer as part of the Long Island Breast Cancer Study Project, urine samples were collected within 3 months of diagnosis and several phthalate metabolites were measured. The women were then followed for a median of 17.6 years.

- Levels of metabolites of DEHP, a phthalate that acts as an anti-androgen, were associated with breast cancer specific mortality in a manner that was moderated by body weight (body mass index or BMI). For women with BMI scores in the normal or lower weight ranges, higher DEHP metabolite levels were associate with higher mortality rates. On the other hand, for women in the higher (overweight and obese) BMI ranges, there was an inverse relationship between the metabolite levels and breast cancer specific mortality rates.[24]

Who is most likely to be exposed to phthalates?

Historically, women have had slightly higher exposures to phthalates than men; however, because phthalates have become ubiquitous in our environment, used now in everything from personal care products to industrial adhesives and building materials, everyone is equally at risk for exposure. Data collected from a nationally representative population show which subgroups of the population are most likely to be exposed to which phthalates[25]:

- Exposure to BzBP, DBP, DEHP and DMP is highest in children ages 6 to 11.

- Exposure to DEP, used as a solvent in many products containing fragrance (e.g., perfume, deodorant, soaps and shampoos) is typically highest in men and women age 20 years and older, followed closely by 12- to 19-year-olds.

- Data also show that non-Hispanic blacks have higher levels of phthalates than do non-Hispanic whites.

Who is most vulnerable to the health effects of phthalates?

While everyone should be concerned about exposure to phthalates, some of us are more vulnerable to adverse health outcomes than others. Fetuses and infants, who are at critical stages of development, are particularly sensitive to phthalate exposure.[26],[27] Young girls exposed to high levels of phthalates are also at risk of negative health effects.[28] Because phthalates can cross the placenta and are present in and can be transmitted though breast milk,[29] it is important that women of child-bearing age, pregnant women and mothers who are breast-feeding avoid phthalate exposure.

What are the top tips to avoid exposure?

Phthalates are ubiquitous in our environment and very hard to avoid. Here are a few tips to help you reduce your exposure:

- Become a label reader: Avoid buying personal care products that contain “fragrance” or “perfume.” Choose nail polish that is phthalate free and bring your own polish to the nail salon if they don’t offer a phthalate-free option. These are typically labeled “DBP-free” or “Toxic Trio Free.”

- Avoid plastics for food prep and storage: Food containers made from PVC plastics (i.e., number 3 plastics) contain phthalates, as do vinyl plastic cooking utensils, plastic food storage containers and plastic food packaging.[30],[31]

- Use glass, ceramic or metal for storage and preparation of hot foods. Avoid hot foods packaged in plastic. Microwave in glass or ceramic, never in plastic.

- Choose natural materials for your home. Avoid vinyl shower curtains, vinyl flooring, plastic window treatments, and vinyl replacement windows.

- Avoid fragrances and air fresheners. FDA regulations do not require companies to list fragrance components on ingredient labels, because fragrance formulations are considered proprietary. Phthalates (especially DEP) are often added to fragrance to make the scent linger. As a result, fragrances, perfumes and scented lotions, soaps and other products can contain phthalates. Limit your use of perfumes. Avoid using artificial air fresheners such as plug-ins, sprays or artificially scented candles. Look for naturally scented candles to freshen your home, or cut some fresh flowers, or simply open a window!

Updated 2021

[1] Cirillo, T., Fasano, E., Castaldi, E., Montuori, P., & Amodio Cocchieri, R. (2011). Children’s exposure to Di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate and dibutylphthalate plasticizers from school meals. J Agr Food Chem, 59(19), 10532–10538.

[2] Gao, C-G. and Kannan, K. “Phthalates, bisphenols, parabens, and triclocarban in feminine hygiene products from the United States and their implication for human exposures.” Environment International 136 (2020): 105465. doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2020.105465

[3] Rudel, R., Brody, J., Spengler, J., Vallarino, J., Geno, P., Sun, G., & Yau, A. (2001). Methods to detect selected potential mammary carcinogens and endocrine disruptors in commercial and residential air and dust samples. J Air Water Manag Assoc, 51, 499–513.

[4] Schettler, T. (2005). Human exposure to phthalates via consumer products. Int J Androl, 29, 134–139.

[5] Janjua NR, Frederiksen H, Skakkebaek NE, et al. (2008). Urinary excretion of phthalates and paraben after repeated whole-body topical application in humans. Int J Androl, 31:118-130.

[6] Lopez-Carillo, L. et al. “Exposure to phthalates and breast cancer risk in northern Mexico.” Environmental Health Perspectives 118, 4 (2010): 539-544. doi:10.1289/ehp.0901091

[7] Wu, A. et al. “Urinary phthalate exposures and risk of breast cancer: the Multiethnic Cohort study.” Breast Cancer Research 23 (2021): 44. doi.org/10.1186/s13058-021-01419-6

[8] Kang SC, Lee BM (2005). DNA methylation of estrogen receptor α gene by phthalates. J Toxicol Environ Health, 68:1995-2003.

[9] Fang, H., Tong, W., Branham, W. S., Moland, C. L., Dial, S. L., Hong, H., … Sheehan, D. M. (2003). Study of 202 Natural, Synthetic, and Environmental Chemicals for Binding to the Androgen Receptor. Chem Res Toxicol, 16(10), 1338–1358.

[10] Hsieh, T.-H., Tsai, C.-F., Hsu, C.-Y., Kuo, P.-L., Lee, J.-N., Chai, C.-Y., … Tsai, E.-M. (2012). Phthalates induce proliferation and invasiveness of estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer through the AhR/HDAC6/c-Myc signaling pathway. FASEB Journal, 26(2), 778–787.

[11] Tranfo G., et al., Urinary phthalate monoesters concentration in couples with infertility problems. Toxicology Letters, vol. 213, pp 15-20, 2012. Abstract Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22197707. August 18, 2014.

[12] Chou, Y., Huang, P., Lee, C., Wu, M., & Lin, S. (2009). Phthalate exposure in girls during early puberty. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab, 22, 69–77.

[13] Steingraber, S. (2007). The Falling Age of Puberty in U.S. Girls: What We Know, What we Need to Know. San Francisco: Breast Cancer Fund.

[14] Kim IY, Han SY, Moon A (2004a). Phthalates inhibit tamoxifen-induced apoptosis in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. J Toxicol Environ Health, 67:2025-2035.

[15] Gwinn, M., Whipkey, D., Tennant, L., & Weston, A. (2007). Gene expression profiling of di-n-butyl phthalate in normal human mammary epithelial cells. J Environ Pathol Toxicol Oncol, 26, 51–61.

[16] Crobeddu,B et al. “Di(2ethylhexyl) phthalates (DEHP) increases proliferation of epithelial breast cancer cells through progesterone receptor disregulation.” Environmental Research 173 (2019): 165-173. doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2019.03.037

[17] Foster, P. (2005). Disruption of reproductive development in male rat offspring following in utero exposure to phthalate esters. Int J Androl, 29, 140–147.

[18] Latini G, Del Vecchio A, Massaro M, et al. (2006). Phthalate exposure and male infertility. Toxicol, 226:90-98.

[19] Swan, S., Main, K., Liu, F., Stewart, S., Kruse, R., Calafat, A., … Teague, J. (2005). Decrease in anogenital distance among male infants with prenatal phthalate exposure. Environ Health Persp, 113, 1056–1061.

[20] Lind, PM., Zethelius, B., Lind, L. (2012). Circulating levels of phthalate metabolites are associated with prevalent diabetes in the elderly. Diabetes Care. 1935-5548.

[21] Bornehag and Nanberg. Phthalate exposure and asthma in children. Int J Androl. 2010 Apr;33(2):333-45.

[22] Bornehag et al. The association between asthma and allergic symptoms in children and phthalates in house dust: a nested

case-control study. EHP. 2004 Oct;112(14):1393-1397.

[23] Kim and Park. Phthalate exposure and childhood obesity. Ann Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2014 Jun; 19(2):69-75.

[24] Parada, Humberto Jr et al. “Urinary Phthalate Metabolite Concentrations and Breast Cancer Incidence and Survival following Breast Cancer: The Long Island Breast Cancer Study Project.” Environmental Health Perspectives 126, 4 047013. 26 Apr. 2018, doi:10.1289/EHP2083.

[25] CDC: Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (2005). Fourth National Report on Human Exposure to Environmental Chemicals. Atlanta: Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

[26] Wittassek, M., Angerer, J., Kolossa-Gehring, M., Schafer, S., Klockenbusch, W., Dobler, L., … Wiesmuller, G. (2009). Fetal exposure to phthalates: a pilot study. Int J Hyg Environ Health, 212, 492–498.

[27] Swan, S., Main, K., Liu, F., Stewart, S., Kruse, R., Calafat, A., … Teague, J. (2005). Decrease in anogenital distance among male infants with prenatal phthalate exposure. Environ Health Persp, 113, 1056–1061.

[28] Chou, Y., Huang, P., Lee, C., Wu, M., & Lin, S. (2009). Phthalate exposure in girls during early puberty. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab, 22, 69–77.

[29] Hines, E., Calafat, A., Silva, M., Mendola, P., & Fenton, S. (2009). Concentrations of phthalate metabolites in milk, urine, saliva, and serum of lactating North Carolina women. Environ Health Persp, 117, 86–92.

[30] Rudel, R. A., Gray, J. M., Engel, C. L., Rawsthorne, T. W., Dodson, R. E., Ackerman, J. M., … Brody, J. G. (2011). Food packaging and bisphenol A and bis(2-ethyhexyl) phthalate exposure: findings from a dietary intervention. Environ Health Persp, 119(7), 914–920.

[31] Ji, K., Lim Kho, Y., Yoonsuk, P., Kyungho, C. (2010). Influence of a five-day vegetarian diet on urinary levels of antibiotics and phthalate metabolites: a pilot study with “Temple Stay” participants. Environ. Res. 110(4), 375-382.