Air Pollution and Breast Cancer Study

At a Glance

A recent University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) study examining 16 hazardous chemicals in air pollution in the Los Angeles area and found that LA women face unsafe levels of exposure to hazardous air pollutants, and women of color bear a disproportionate breast cancer burden from exposure. Few studies have examined breast cancer risk from air toxics among urban, diverse communities like this.

Introduction

The air has many types of pollutants from a range of sources. In addition to the traffic and particulate pollutants in the air, hazardous chemicals are in the mix. A hazardous air pollutant (HAP) or toxic air contaminant (TAC) is a chemical that causes cancer, reproductive harm, or other serious health effects resulting in disease and death. [1] These chemicals come from many sources including both traffic and non-traffic sources such as gas wells, hazardous waste sites, landfills, and polyvinyl chloride (PVC) manufacturing plants.

Few studies have examined breast cancer risk from air toxics among urban, diverse communities. Fenceline communities live near hazardous waste sites, gas wells, landfill sites, freeways, and ports and are affected by chemical emissions, noise, odors, and traffic. Fenceline communities in urban areas are particularly impacted by air pollutants including traffic, fossil fuel extraction, plastic and petroleum chemical emissions, landfills, waste incineration, and hazardous waste sites.

Research shows that the distribution of air pollution is disproportionately higher in communities of color compared to white communities. The NAACP report “Coal Blooded: Putting Profits Before People” found that 78% of all African Americans live within 30 miles of a coal-fired power plant.

The cumulative effects of being exposed to many air pollutants over many years can be particularly damaging to our health. Affected communities face many hazards from living near chemical emissions, but few breast cancer studies have examined breast cancer risk associated with exposure to hazardous air pollutants.

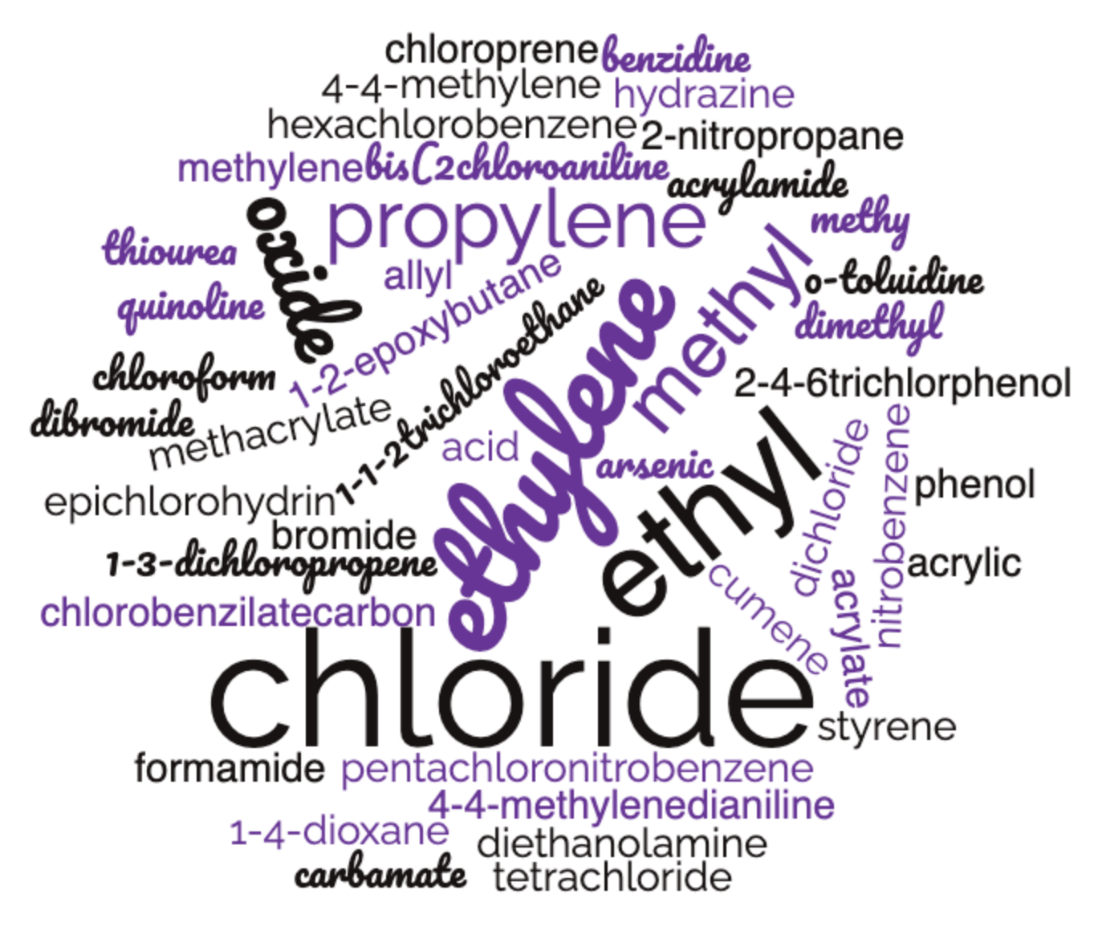

Learn About the Chemicals in This Study

All chemicals of concern included in this study are fossil fuel chemicals.

- Polyvinyl chemicals- vinyl chloride and ethylene dichloride are used to manufacture polyvinyl chloride (PVC) plastic and vinyl products. Vinyl chloride is a colorless gas released from landfills, sewage treatment plants, and hazardous waste sites. Vinyl chloride is genotoxic, inducing unscheduled DNA synthesis, increasing the frequency of sister chromatid exchange in rat and human cells, and increasing the frequency of chromosomal aberrations and micronucleus formation. Knowledge of the human carcinogenicity of vinyl chloride stems largely from several extensive occupational cohort studies of polyvinyl chloride manufacturing workers. Still, these studies included few women and knowledge about breast cancer impacts is lacking. Multiple animal studies have observed that inhalation of vinyl chloride increases the incidence of mammary tumors in mice, rats, and hamsters. [3] The US EPA classifies ethylene dichloride as a probable human carcinogen. [5-7]

- Vinyl acetate is used for plastic and adhesives production in the preparation of polymers and copolymers (Daniels, 1983). The US EPA classifies ethylene dichloride as a probable human carcinogen. [5-7] Vinyl acetate has not been classified by the US EPA but has been designated as possibly carcinogenic to humans by the International Agency for Research on Cancer based on the following health effects:

- (i) Vinyl acetate is rapidly transformed into acetaldehyde in human blood and animal tissues.

- (ii) There is sufficient evidence in experimental animals for the carcinogenicity of acetaldehyde (IARC, 1987b). Both vinyl acetate and acetaldehyde induce nasal cancer in rats after administration by inhalation.

- (iii) Vinyl acetate and acetaldehyde are genotoxic in human cells in vitro and in animals in vivo.

- 1,1,2,2 tetrachloroethane is used as a common manufacturing byproduct in the process of catalytic chlorination. A study in experimental animals reported increased mammary gland fibroadenoma with 1,1,1,2-tetrachloroethane exposure. In humans, 1,1,1,2-tetrachloroethane accumulates in fat tissue; it appears genotoxic, but studies are limited. This toxicant is an understudied exposure; a 2014 IARC review did not identify any carcinogenicity studies in humans. [4]

- Traffic-related chemicals- formaldehyde, benzene, ethylbenzene, toluenes, xylenes, and 1,2-butadiene come from power plant emissions, gas well emissions, and vehicle emissions (Figure 1). Together they are categorized as volatile organic compounds (VOCs). They come from natural sources, such as fire burning; however, human activity has been the main sources of prevalent VOCs in the air. Because of their biological structures and their easy volatilization, they easily enter our blood and lymph through inhalation, skin absorption, and orally through polluted water or food. Several studies point to their known association with various health and environmental consequences, including neurological impairment. Research indicates that even at low concentrations, VOCs can trigger a range of health issues, such as nausea, eye and throat irritation, the onset of asthma attacks, fatigue, dizziness, and cognitive impairment. Furthermore, persistent VOCs may also lead to cancer, pulmonary disease, skin problems, and immunological system disorders. [18-22]

What We’re Doing

Recent studies have demonstrated that traffic-related air pollutants can increase breast cancer risk. However, there are additional hazardous air pollution compounds that come from industrial emissions that we know less about. The scientific literature also lacks data on the impact of hazardous air pollutant exposure on ethnically diverse groups of women in urban environments as previous studies have oversampled white, rural areas.

For the UCLA Air Toxics Study, researchers examined 16 hazardous chemicals in air pollution in the Los Angeles area. [2] This study tracked breast cancer occurrence among Multiethnic Cohort participants from 1993-1996 through 2013 associated with air pollution data from the National-Scale Air Toxics Assessment 1998-2003 data.

Researchers used the levels of hazardous air pollutants to track exposure levels and breast cancer rates to ask the questions: Does the likelihood of breast cancer increase from exposure to hazardous air pollutants among women in Los Angeles? And how do breast cancer rates differ across race and ethnicity?

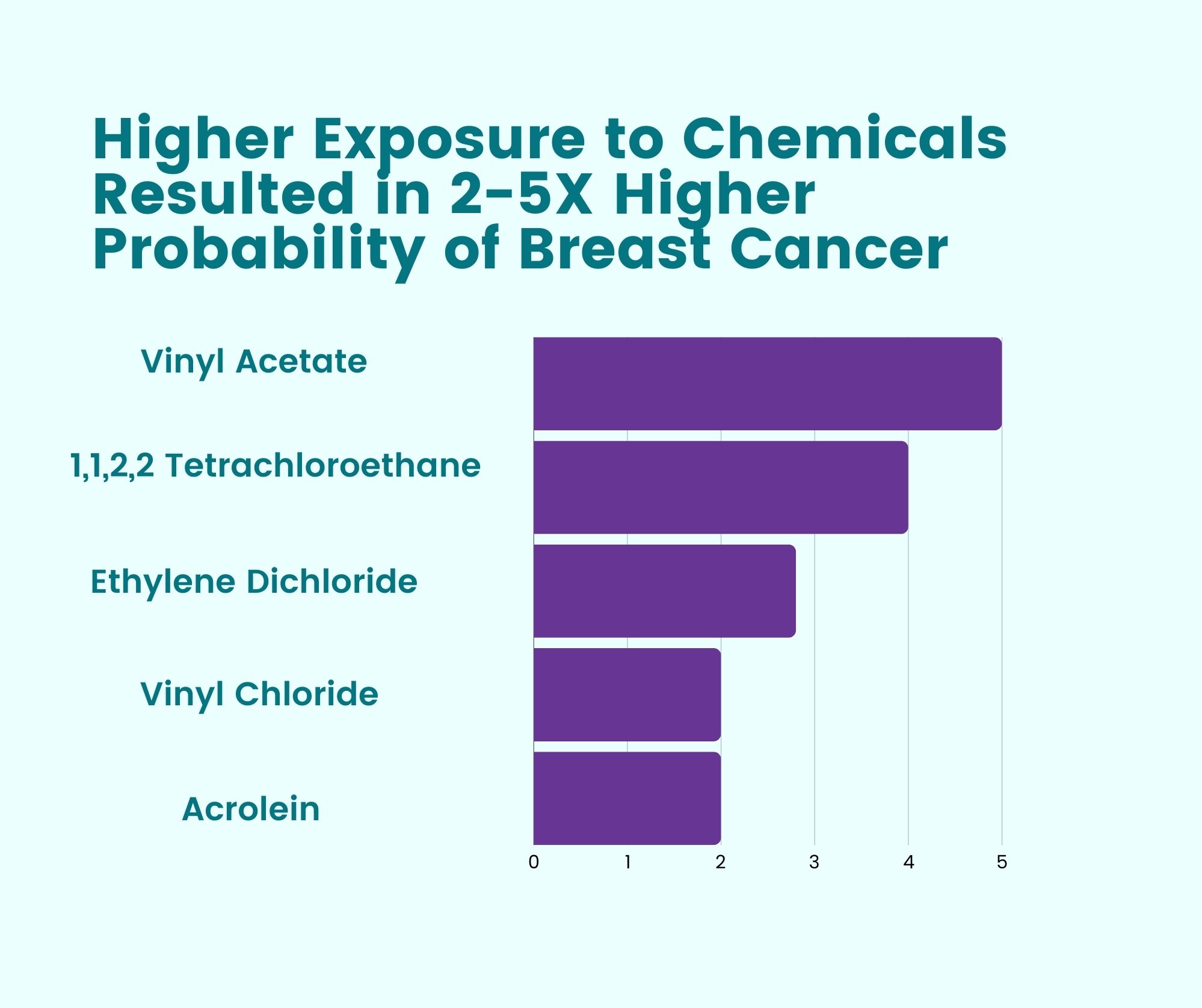

Figure 1. Exceess probability of of getting breast cancer over a 20-year period [2]

Results found that among women from the Greater Los Angeles area (n=48,723), hazardous air pollutants significantly increased the likelihood of breast cancer. Researchers chose hazardous chemicals that are endocrine disruptors or mammary gland carcinogens (Figure 1). Of 16 studied, 14 hazardous chemicals significantly increased the likelihood of getting breast cancer over the 20-year study period:

- 6 of 11 hazardous chemicals came from traffic, gas wells, and fossil fuel power plant emissions (xylene exposure presented the highest breast cancer likelihood)

- 8 of 11 came from manufacturing, landfill, and hazardous waste emissions (vinyl acetate, vinyl chloride, ethylene dichloride, and 1,1,2,2 tetrachloroethane exposure presented the highest breast cancer likelihood)

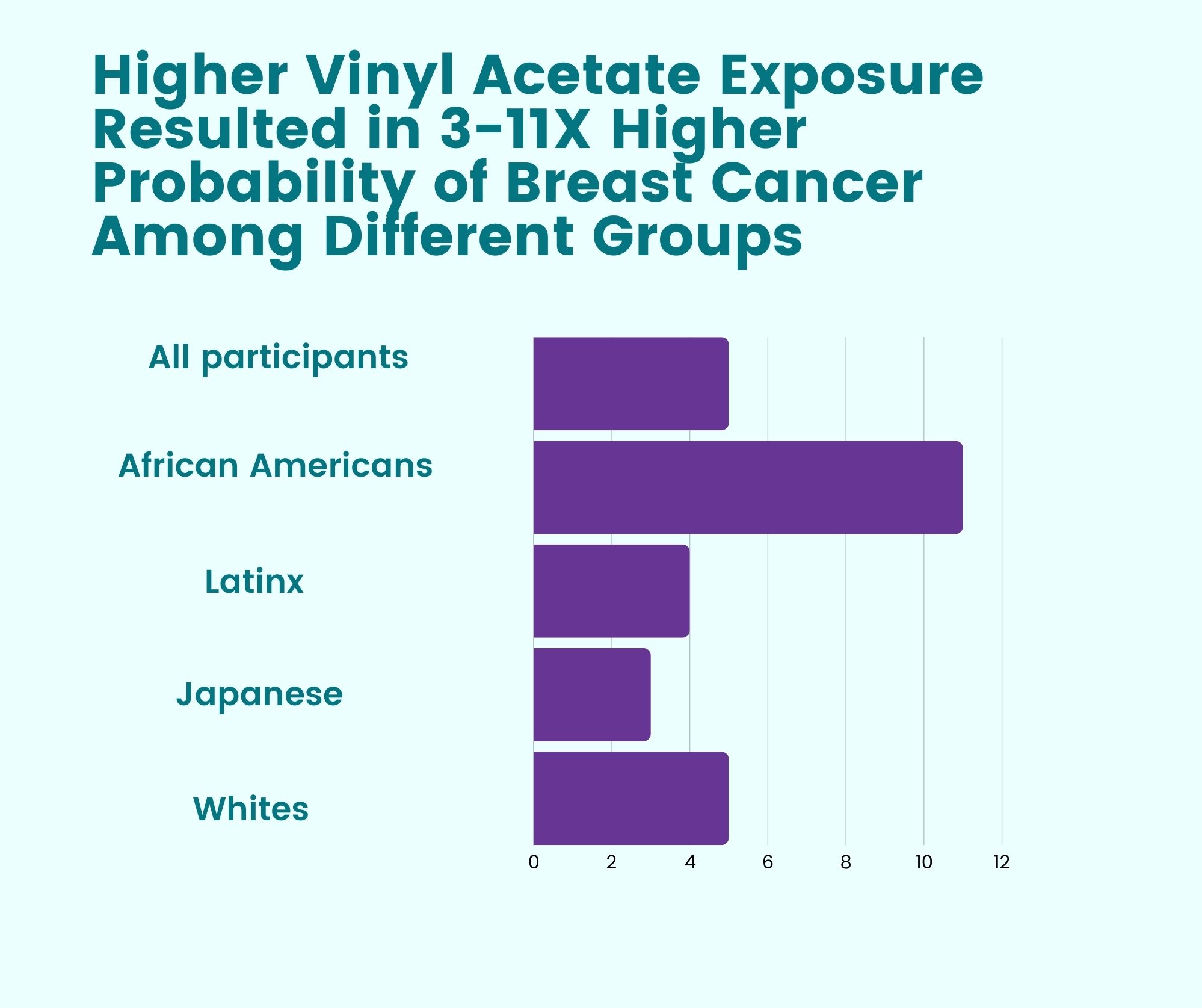

- Increases in the likelihood of breast cancer from hazardous air pollutants were greatest for women of color (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Differences in Breast Cancer Risk by Race/Ethnicity [2]

Key Takeaways

Out of 181 toxic air pollutants that were considered for inclusion, UCLA researchers selected 57 agents identified as endocrine disruptors or suspected/established carcinogens. 16 of 57 were analyzed and 14 of the 16 significantly increased breast cancer likelihood. The remaining 41 endocrine disruptors and breast carcinogens were not included in this analysis due to lack of unexposed cases (Figure 3). This means that there were not enough people with breast cancer who were less exposed to these chemicals to measure the impact of chemical exposure. This was particularly the case among African Americans, for whom estimates could not be made due to the lack of sufficient number of unexposed cases in case of three chemicals (1,1,2,2 tetrachloroethane, ethylene dichloride, and vinyl chloride). Based on the outcomes of this study, these remaining endocrine disruptors and breast carcinogens deserve further attention.

Figure 3. More study is needed to understand the breast cancer risk associated with these additional 41 mammary carcinogens and endocrine disrupting chemicals.

A key finding of this study is that the highest chemical exposure levels were not associated with the highest likelihood of getting breast cancer over the 20-year study period. Rather, the lowest levels of exposure from industrial hazardous air pollutants were associated with the greatest increases in likelihood of getting breast cancer. The highest risks came from vinyl acetate, 1,1,2,2-tetrachloroethane, and polyvinyl chemicals, all of which both had low exposure levels. This finding highlights the need to evaluate the health effects from low levels of exposure due to their ability to disrupt the endocrine system, which can lead to breast cancer.

How did the UCLA Multiethnic Cohort study results compare to previous studies?

The most significant difference is that study participants herein were diverse and from an urban environment. The UCLA Multiethnic Cohort study had high traffic and industrial pollutant levels, as well as high pollution burden in neighborhoods with a high concentration of historically marginalized racial and ethnic groups which suggests that chemical exposure levels varied between the UCLA study and two previously published studies on this topic. [2]

Summary

In summary, these study results provide evidence that women in Los Angeles face unsafe levels of exposure to hazardous air pollutants, and that women of color bear a disproportionate breast cancer burden from exposure. Areas and individuals who’ve experienced historical environmental injustices due to the location of polluting industrial and waste disposal sources are at a disproportionately higher risk of breast cancer. Cumulative exposure (exposure to multiple chemicals) and aggregate exposure (exposures across multiple routes including oral, dermal, inhalation, and placental) to hazardous air pollutants remain a concern and present potent risk factors for breast cancer, particularly for vulnerable communities of color and fenceline communities. These findings show the importance of monitoring and mitigating hazardous air pollutants, even at low levels, to prevent breast cancer.

Policy Recommendations

Based on these and previous findings, women and communities of color are warranted greater protection from hazardous air pollutants including vinyl acetate, 1,1,2,2 tetrachloroethane, ethylene dichloride, vinyl chloride, acrolein, acetaldehyde, xylenes, benzene, toluene, formaldehyde, ethylbenzene, 1,3-butadiene, naphthalene, and trichloroethylene to lower their disproportionately high risk of breast cancer.

All policy and regulatory advances in the areas of hazardous chemical and plastic production reductions, fossil fuel emissions reductions, transit justice, transportation electrification, and anti-redlining will be beneficial to communities in that these actions lower exposure to both traffic-related and hazardous air pollutants. Areas of high priority that hold the potential to better protect our communities include:

- Addressing exposure to chemicals used in plastic and PVC manufacturing (vinyl acetate, vinyl chloride, ethylene dichloride) and catalytic chlorination (1,1,2,2 tetrachloroethane). These exposures presented the most significant increases in statistical probability of getting breast cancer in this study. These chemicals should be reviewed for phaseout with urgency.

- The scientific regulatory community needs to prioritize low-dose exposures to address the importance of exposure to breast cancer carcinogens and endocrine-disrupting chemicals in efforts to regulate chemicals aimed at preventing disease. The data herein document that the three chemicals that caused greatest increases in likelihood of breast cancer (vinyl acetate, 1,1,2,2 tetrachloroethane, vinyl chloride and ethylene dichloride) were at the lowest levels of exposure.

On a national and international scale, policy actions to limit/ban the production, use, and distribution of PVC will benefit fence line communities and communities of color, who are disproportionately exposed to hazardous chemicals. Vinyl chloride and ethylene dichloride are two chemicals needed to make PVC and are hazardous air pollutants that significantly increase breast cancer risk. Approximately 90% of the ethylene dichloride produced is dedicated to making vinyl chloride monomer, the chemical precursor to PVC. [17] Banning PVC plastic in the US would have global benefits on the environment and cancer.

Take action now to tackle carcinogenic plastics!

Additional Resources

- Take action to tackle carcinogenic plastics!

- Learn about oil drilling in California | NY Times

- Learn about air pollution and the climate: Air Pollution 101 | National Geographic

- National Air Toxics Assessment | US EPA

- Human Health Risk Assessment | Department of Toxic Substances Control (ca.gov)

- Environmental Racism in America: An Overview of the Environmental Justice Movement and the Role of Race in Environmental Policies – Goldman Environmental Prize (goldmanprize.org)

- Coal Blooded: Putting Profits Before People | NAACP

- CARB Identified Toxic Air Contaminants | California Air Resources Board

Our Partners On Air and Breast Cancer

Department of Epidemiology, School of Public Health, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, College of Health and Public Service, University of North Texas, Denton, TX, USA, Center for Racial and Ethnic Equity in Health and Society, University of North Texas, Denton, TX, USA, Department of Preventive Medicine, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, University of California, San Francisco, CA, University of California, San Francisco Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center, San Francisco, CA

Footnotes

[1] Hazardous air pollutants | US EPA. Accessed October 1, 2023. https://www.epa.gov/haps.

[2] Heck, J.E., He, D., Wing, S.E., Ritz, B., Carey, C.D., Yang, J., Stram, D.O., Le Marchand, L., Park, S.L., Cheng, I., Wo, A.H. Exposure to outdoor ambient air toxics and risk of breast cancer: The Multiethnic Cohort. J of International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health 259 (2024) 114362. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1438463924000439.

[3] IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Chemical Agents and Related Occupations. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2012.

[4] IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Trichloroethylene, tetrachloroethylene, and some other chlorinated agents. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2014.

[5] Naphthalene – U.S. environmental protection agency. 2016. Accessed October 1, 2023. https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2016-09/documents/naphthalene.pdf.

[6] Ethylene dichloride (1,2-dichloroethane) – U.S. environmental protection agency. 2017. Accessed October 1, 2023. https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2016-09/documents/ethylene-dichloride.pdf.

[7] Vinyl Acetate – U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 2016. Accessed October 1, 2023. https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2016-09/documents/vinyl-acetate.pdf.

[8] California EPA, Department of Toxic Substances Control, Human and Ecological Risk Office. Human Health Risk Assessment (HHRA) Note 3. June 2020 (Rev May 2022). Accessed October 1, 2023 https://dtsc.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/sites/31/2022/02/HHRA-Note-3-June2020-Revised-May2022A.pdf.

[10] Sandler, Dale P., M. Elizabeth Hodgson, Sandra L. Deming-Halverson, Paula S. Juras, Aimee A. D’Aloisio, Lourdes M. Suarez, Cynthia A. Kleeberger, et al. “The Sister Study Cohort: Baseline Methods and Participant Characteristics.” Environmental Health Perspectives 125, no. 12 (2017). Accessed October 1, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp1923.

[10] Garcia, Erika, Susan Hurley, David O Nelson, Andrew Hertz, and Peggy Reynolds. “Hazardous Air Pollutants and Breast Cancer Risk in California Teachers: A Cohort Study.” Environmental Health 14, no. 1 (2015). Accessed October 1, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-069x-14-14.

[11] Niehoff, Nicole M., Marilie D. Gammon, Alexander P. Keil, Hazel B. Nichols, Lawrence S. Engel, Dale P. Sandler, and Alexandra J. White. “Airborne Mammary Carcinogens and Breast Cancer Risk in the Sister Study.” Environment International 130 (2019): 104897. Accessed October 1, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2019.06.007.

[12] Pastor, Manuel, James L. Sadd, and Rachel Morello-Frosch. “Waiting to Inhale: The Demographics of Toxic Air Release Facilities in 21st-Century California*.” Social Science Quarterly 85, no. 2 (2004): 420–440. Accessed October 1, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0038-4941.2004.08502010.x.

[13] Niehoff, Nicole M., Mary Beth Terry, Deborah B. Bookwalter, Joel D. Kaufman, Katie M. O’Brien, Dale P. Sandler, and Alexandra J. White. “Air Pollution and Breast Cancer: An Examination of Modification by Underlying Familial Breast Cancer Risk.” Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 31, no. 2 (2021): 422–29. Accessed October 1, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.epi-21-1140.

[14] Cheng, Iona, Chiuchen Tseng, Jun Wu, Juan Yang, Shannon M. Conroy, Salma Shariff‐Marco, Lianfa Li, et al. “Association between Ambient Air Pollution and Breast Cancer Risk: The Multiethnic Cohort Study.” International Journal of Cancer 146, no. 3 (2019): 699–711. Accessed October 1, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.32308.

[15] Cushing, Lara, John Faust, Laura Meehan August, Rose Cendak, Walker Wieland, and George Alexeeff. “Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Cumulative Environmental Health Impacts in California: Evidence from a Statewide Environmental Justice Screening Tool (Calenviroscreen 1.1).” American Journal of Public Health 105, no. 11 (2015): 2341–48. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2015.302643.

[16] “1,2-Dibromoethane.” National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem Compound Database, 2021. https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/1_2-Dibromoethane. National Center for Biotechnology Information; 2021.

[17] “EDC in PVC Production.” EDC in PVC production, 2010. https://www.engineeringspecifier.com/around-the-industry/edc-in-pvc-production.

[18] Garte, Seymour, Emanuela Taioli, Todor Popov, Claudia Bolognesi, Peter Farmer, and Franco Merlo. “Genetic Susceptibility to Benzene Toxicity in Humans.” Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part A 71, no. 22 (2008): 1482–89. Accessed October 3, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1080/15287390802349974.

[19] Abbate, C., C. Giorgianni, F. Muna, and R. Brecciaroli. “Neurotoxicity Induced by Exposure to Toluene.” International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health 64, no. 6 (1993): 389–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00517943.

[20] Yu, Chuck Wah, and Jeong Tai Kim. “Building Pathology, Investigation of Sick Buildings — VOC Emissions.” Indoor and Built Environment 19, no. 1 (2010): 30–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/1420326×09358799.

[21] Rolle-Kampczyk UE, Rehwagen M, Diez U, Richter M, Herbarth O and Borte M. “Passive smoking, excretion of metabolites, and health effects: Results of the Leipzig’s Allergy Risk Study (LARS).” Archives of Environmental Health 57, no 4 (2002): 326−31. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/00039890209601416.

[22] Montero-Montoya, Regina, Rocío López-Vargas, and Omar Arellano-Aguilar. “Volatile Organic Compounds in Air: Sources, Distribution, Exposure and Associated Illnesses in Children.” Annals of Global Health 84, no. 2 (2018): 225-238. Accessed October 3, 2023. https://doi.org/10.29024/aogh.910.

[23] Cheng, Iona, Juan Yang, Chiuchen Tseng, Jun Wu, Shannon M. Conroy, Salma Shariff-Marco, Scarlett Lin Gomez, et al. “Outdoor Ambient Air Pollution and Breast Cancer Survival among California Participants of the Multiethnic Cohort Study.” Environment International 161 (2022): 107088. Accessed October 1, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2022.107088.

Types: Fact Sheet