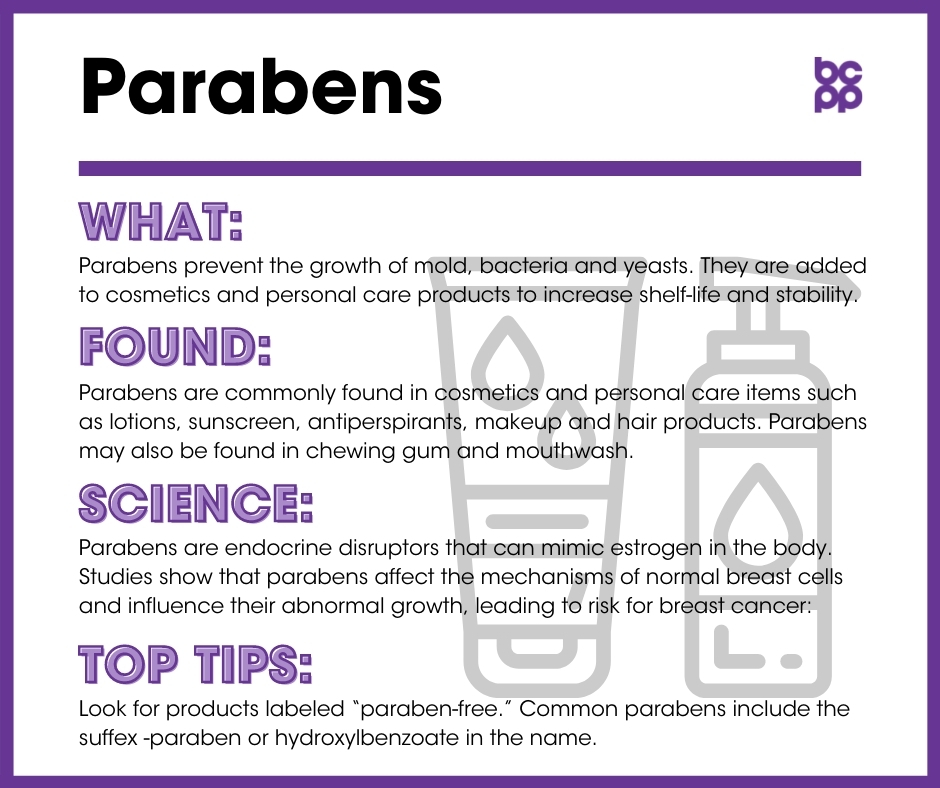

Parabens

At a Glance

Parabens are a group of chemicals that prevent the growth of mold, bacteria and yeasts. They are often added to cosmetics and personal care products to increase shelf-life and stability.

Parabens enter the body through dermal absorption, ingestion and inhalation, and can enhance the actions of the natural estrogen known as estradiol.

What are parabens?

Parabens are a group of compounds widely used as preservatives for their antimicrobial properties. They are commonly added to cosmetics and other personal care products to prevent the growth of mold, bacteria and yeasts. Methylparaben and propylparaben are the most commonly used parabens.[1] Other names for these are methyl 4-hydroxybenzoate and propyl 4-hydroxylbenzoate.[2]

Where are parabens found?

Parabens are most commonly found in cosmetics and personal care items[3] such as lotions, sunscreen, antiperspirants, makeup and hair products. [4],[5],[6] Parabens may also be found in chewing gum and mouthwash.[7]

What evidence links parabens to breast cancer?

Parabens are known endocrine disruptors that can mimic estrogen in the body. Several studies have shown that parabens can affect the mechanisms of normal breast cells and potentially influence their abnormal growth, leading to increased risk for breast cancer:

- Increased cell growth: Several studies show that parabens may mimic estrogen and, as a result, increase breast cell growth.[8],[9] Cell-based studies of parabens’ effects on the estrogen receptor do not address other systems that influence the development of breast cancer. One cell-based study tried to mimic the conditions of cells and tissues by adding proteins called growth factors, which stimulate the expression of HER2, found in 25 percent of breast cancers. The authors found that the presence of a growth factor called heregulin leads parabens to stimulate the estrogen receptor at levels that had been considered non-toxic in cell-based research.[10]

- Decreased cell death: Studies show that some concentrations of parabens may reduce programmed cell death, which is one way the body deals with damaged cells.[11]

- Metastasis: In vitro studies have found that cells exposed to parabens for over 20 weeks may increase factors associated with metastases.[12]

- Blockage of chemotherapy agents: Methylparaben may decrease the ability of tamoxifen to impede the effects of estrogen, making this common chemotherapy drug less effective at treating breast cancer. [13]

Parabens have been linked to other health concerns, such as allergies,[14] and may also disrupt thyroid levels.[15]

Who is most likely to be exposed to parabens?

A recent study looking at a representative cross section of the U.S. population showed that over 90 percent of people in the United States have parabens in their bodies. Higher concentrations were found in women, people in high-income households, and African Americans.[16] Hair products marketed and used by African Americans (such as hair creams, relaxers and stylers) are more likely to contain parabens than products used by whites.[17],[18]

Who is most vulnerable to the health effects?

Pregnant women, fetuses and young children are most vulnerable to parabens, because at these life stages breast tissue is most susceptible to endocrine disruptors.[19]

What are the top tips to avoid exposure?

- Look for products labeled “paraben-free.”

- Avoid products listing parabens as ingredients. Common parabens and their synonyms include:

- propylparaben (or propyl 4-hydroxylbenzoate),

- butylparaben (or butyl 4-hydroxylbenzoate),

- ethylparaben (or ethyl 4-hydroxylbenzoate)

- heptylparaben (or heptyl 4-hydroxylbenzoate),

- methylparaben (or methyl 4-hydroxybenzoate)

- Pay particular attention to products marketed to kids: both the European Commission and Denmark have banned butylparaben and propylparaben from diaper creams and other leave-on products for children under three.[20],[21]

Reviewed 2019

[2] National Center for Biotechnology Information. “PubChem Compound.” Accessed November 17, 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pccompound?term=paraben.

[3] Błędzka, Dorota, Jolanta Gromadzińska and Wojciech Wąsowicz. “Parabens. From environmental studies to human health.” Environment International 67 (2014): 27–42. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2014.02.007.

[4] Konduracka, Ewa et al. “Relationship between everyday use cosmetics and female breast cancer.” Polskie Archiwum Medycyny Wewnetrznej 124, 5 (2014): 264-9. doi:10.20452/pamw.2257.

[5] Stiel, Laura et al. “A review of hair product use on breast cancer risk in African American women.” Cancer Medicine 5, 3 (2016): 597-604. doi:10.1002/cam4.613.

[6] Environmental Working Group. “EWG’s Skin Deep Cosmetic Database.” Last modified September 1, 2020. http://www.ewg.org/skindeep/browse.php?containing=703937&order=webscore_DESC&&showmore=products&start=10.

[7] Larsson, Kristin et al. “Exposure determinants of phthalates, parabens, bisphenol A and triclosan in Swedish mothers and their children.” Environment International 73 (2014): 323-33. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2014.08.014.

[8] Darbre, Philippa D, and Philip W Harvey. “Parabens can enable hallmarks and characteristics of cancer in human breast epithelial cells: a review of the literature with reference to new exposure data and regulatory status.” Journal of Applied Toxicology 34, 9 (2014): 925-38. doi:10.1002/jat.3027.

[9] Pan, Shawn et al. “Parabens and Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Ligand Cross-Talk in Breast Cancer Cells.” Environmental Health Perspectives 124, 5 (2016): 563-9. doi:10.1289/ehp.1409200.

[10] Pan, Shawn et al. “Parabens and Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Ligand Cross-Talk in Breast Cancer Cells.” Environmental Health Perspectives 124, 5 (2016): 563-9. doi:10.1289/ehp.1409200.

[11] Darbre, Philippa D, and Philip W Harvey. “Parabens can enable hallmarks and characteristics of cancer in human breast epithelial cells: a review of the literature with reference to new exposure data and regulatory status.” Journal of Applied Toxicology 34, 9 (2014): 925-38. doi:10.1002/jat.3027.

[12] Darbre, Philippa D, and Philip W Harvey. “Parabens can enable hallmarks and characteristics of cancer in human breast epithelial cells: a review of the literature with reference to new exposure data and regulatory status.” Journal of Applied Toxicology 34, 9 (2014): 925-38. doi:10.1002/jat.3027.

[13] Darbre, Philippa D, and Philip W Harvey. “Parabens can enable hallmarks and characteristics of cancer in human breast epithelial cells: a review of the literature with reference to new exposure data and regulatory status.” Journal of Applied Toxicology 34, 9 (2014): 925-38. doi:10.1002/jat.3027.

[14] Savage, Jessica H et al. “Urinary levels of triclosan and parabens are associated with aeroallergen and food sensitization.” The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 130, 2 (2012): 453-60.e7. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2012.05.006.

[15] Koeppe ES et al. “Relationship between urinary triclosan and paraben concentrations and serum thyroid measures in NHANES 2007-2008.” The Science of the Total Environment 445-446 (2013): 299-305. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.12.052.

[16] Calafat, Antonia et al. “Urinary concentrations of four parabens in the U.S. population: NHANES 2005-2006.” Environmental Health Perspectives 118, 5 (2010): 679–685. doi:10.1289/ehp.0901560.

[17] Calafat, Antonia et al. “Urinary concentrations of four parabens in the U.S. population: NHANES 2005-2006.” Environmental Health Perspectives 118, 5 (2010): 679–685. doi:10.1289/ehp.0901560.

[18] Stiel, Laura et al. “A review of hair product use on breast cancer risk in African American women.” Cancer Medicine 5, 3 (2016): 597-604. doi:10.1002/cam4.613.

[19] Interagency Breast Cancer and Environmental Research Coordinating Committee (IBCERCC). “Breast Cancer and the Environment: Prioritizing Prevention.” Last modified Feburary 2013. http://www.niehs.nih.gov/about/assets/docs/ibcercc_full_508.pdf.

[20] Konduracka, Ewa et al. “Relationship between everyday use cosmetics and female breast cancer.” Polskie Archiwum Medycyny Wewnetrznej 124, 5 (2014): 264-9. doi:10.20452/pamw.2257.

[21] European Commission. “Press Release: Consumers: Commission improves safety of cosmetics.” September 26, 2014. http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-14-1051_en.htm.